Supporting authors:

- Ahmad Al-Musa

- Karen Chapple

- Lauren Shiga

- Nima Ashtari

- Priya Perwani

Missing Middle (MM) is a form of medium-density development that can fit into lots formerly zoned for single-family housing. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), as part of its Housing Supply Challenge Round 5: Level-Up, engaged U of T’s School of Cities to provide research support for 18 housing innovators. Some of our research work in collaboration with these innovators is available on a webpage that includes:

- Tracking Gentle Density: Mapping new accessory dwelling units (ADUs –additional homes within or adjacent to existing ones) across multiple Canadian cities

- Scaling Up Modular Construction: With an emphasis on how construction companies, modular providers, and developers can work together more effectively

- Big Ideas for Small Town Affordable Homes: How pre-approved designs can help enable small apartment buildings, especially in regional Canada

- Enabling the Missing Middle: Evidence, barriers, enablers and promising practices across Canada

What is the Missing Middle (MM) and why is it important?

Over the past 50 years, North American cities have been increasingly dominated by a duopoly between sprawling single-family homes and a concentration of high-rise development, both dominated by large developers. MM disrupts this duopoly. While primarily referring to middle density (between ‘low rise’ and ‘high rise’), MM is also associated with a moderate to median price point1 and a home size range between studio or one-bedroom apartments in high-rises, and four- or five-bedroom single-family homes. With additional subsidies, including free land, application and development tax waivers, and senior government grants and financing, MM developments can meet the needs of low-income households who are most in need of affordable housing. Unlike large-scale development, MM can be undertaken by small and medium-sized enterprises (SME), encouraging innovation and a new generation of local developers.

Some MM development types include:

- accessory dwelling units (ADUs), either detached or attached to existing homes;

- multiplexes, either subdivided from existing homes or in new build;

- small apartment buildings under four storeys (some Canadian jurisdictions include apartment buildings of up to six storeys on single lots as MM)

Increasingly, single-family homes are not affordable to young households, including those with children, and they are also not suitable for students, seniors, and other smaller households who struggle to find adequate housing options near jobs and services2. In most cities, property owners could improve their own housing affordability by adding units to existing properties, with the potential of generating rent income to cover mortgage costs or supplementing pensions for senior homeowners.

MM developments also have significantly lower embodied greenhouse gas emissions per bedroom – as they rely on existing infrastructure and municipal services – and they improve connectivity, mobility, and mental and physical health impacts for their residents. For these reasons, urban infill has been encouraged for many decades, but cities have not successfully enabled the scaling of MM.

Evidence that MM reform can create affordable homes

There is strong evidence that comprehensive municipal and regional reforms to increase MM can have an immediate impact on development activity. Together the City of Portland and the State of Oregon have actively pursued affordable MM strategies, ranging from municipal targets to subsidies for new low-income affordable ADUs. MM housing units comprised 13.4% of the permit units in Portland in the 67 months from January 2016 to July 2021. Their share increased to 44.7% in the 24 months following the adoption of the Residential Infill Project in 2021.

There is equally strong evidence that increasing infill options can lead to more affordable supply, including for low-income households. Auckland, New Zealand, became the first city to broadly upzone from single-family to as-of-right multiplexes in 2016, with permissive design parameters. Six years later, rents had significantly decreased in relation to income and to other New Zealand cities, including rents in the lowest quartile.

Missing Middle enablers

Our report suggests a typology of enablers that work together to reshape MM development.

1. Targets

Ambitious municipal housing supply targets, especially those attached to conditional funding by provinces and the federal government, can boost approvals and construction. They should include sub-targets that recognize those most in need, ranging from Indigenous households to students, people with disability, and single parents. The federal government is introducing a municipal housing supply needs assessment template influenced by UBC’s Housing Assessment Resource Tool that prioritizes households in core housing need (in unaffordable, overcrowded and/or poorly repaired dwellings) or at risk of homelessness. This needs to be supported by MM policies that encourage small-scale nonmarket and affordable housing in established neighbourhoods.

One good practice is Austin’s 2019 Affordability Unlocked bonusing program. It offers additional density, funding and loans to enable housing affordable to low and moderate-income households. Over 10,000 low-cost units have been produced from this program, and Austin has recorded lower rent increases compared to the rest of Texas.

2. Ending exclusionary zoning

Federal and provincial supply targets motivate municipalities to upzone from prevailing zoning practices, which have effectively excluded most households from neighbourhoods well served with jobs, public transit, and amenities such as parks.

Zoning for MM works best when permissive as to number of units – for instance allowing the legalization of congregate housing options such as rooming houses, group homes, and long-term care. Mixed-use zoning can also enable better communities, with workplaces, corner shops, and childcare centres interspersed with housing.

3. Real local democracy

Most multi-unit development applications face costly, time-consuming, and highly politicized processes, rampant with NIMBY opposition. Zoning reforms allow “as of right” staff approvals of developments conforming to simplified and more permissive rules.

Another democratic municipal planning practice is based in upfront decision-making that starts from the rights-based premise that everyone deserves an affordable, well-located home, and uses mechanisms such as citizen juries determined by representative sampling of local populations to develop inclusive plans.

MM tends to attract small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) developers, including homeowner developers. Edmonton, Kelowna, and Kitchener all have one page ‘how to’ lists for small scale MM development. These cities also promote co-learning partnerships between city staff, SME developers, and financers to problem-solve around MM barriers.

4. Modernizing building codes

Revisions to building codes, preferably at the most powerful (federal) level, can enable MM housing typologies, while different interpretations of regulations across municipal and provincial boundaries restrict replicable designs and hamper faster approval and construction processes.

As is the case in most of the world, B.C. is now allowing single egress for small apartment buildings up to six floors. Single egress allows larger three-plus bedroom units across smaller floorplates, improves cross ventilation, reduces energy consumption, and controls cost. Allowing smaller and much less expensive elevators that still allow for a mobility device would further improve accessibility of small apartment buildings.

5. Eliminating site design barriers

Site design regulations determine feasibility of the developments on small lots, ranging from minimum parking requirements to inflexible front, rear, side and building setbacks. The federal government is encouraging parking reforms, especially in areas with good transit, through its Housing Accelerator Fund program. B.C. recommends introducing parking maximums instead of parking minimums, while Edmonton, Vancouver, and Toronto eliminated them in transit-oriented neighbourhoods, letting market mechanisms decide how much parking is necessary.

Relaxing entrance position residences without compromising emergency access can enable ADU ‘courtyard clusters’ with shared green spaces. Moving to a minimum water-permeable surface ratio, rather than minimum setbacks and floor area ratios, is more likely to aid tree retention, reduce flooding risk, and support pre-approved replicable designs.

6. Rapid approvals

Average approval times range from five months in Charlottetown to 32 months in Toronto, whereas in Kelowna, pre-approved designs can be approved in ten days. ‘Staff days per unit approved’ can be five to ten times higher for smaller applications (3-50 units) than for larger applications (400-500 homes), a huge break to MM development. Onerous requirements for multiple pre-application studies can be waived for smaller MM proposals.

7. Eliminating development taxes

Development taxes, from school and park levies to more generalized development charges, were introduced in the 1970s to pay for large suburban subdivisions in greenfield areas. While inappropriate for urban infill, these ‘growth paying for growth’ costs have increased to the point where they are described as the biggest barrier to development by city staff and developers. Development tax relief for nonmarket developers is a good start practiced by many Canadian cities – but national tax reform for essential infrastructure improvements benefiting all urban residents must be undertaken by the federal government.

8. Financial enablers

Homeowners and small start-up developers, including nonmarket providers, generally have limited equity and lack of development experience. This creates a perception of risk to lenders. Financing may not fall in the municipalities’ direct control, but they can offer support. For instance, Vancouver provides free leased land to nonmarket developers, and the federal government recently pledged low-rate financing for homeowner developers.

Another innovative financing approach involves municipalities acting as co-borrowers to help equity-rich but cash-poor retirees fund renovations or new construction. The Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) in San Diego subsidize low-to moderate-income housing development and establishe housing trust funds.

Promising practices in Canada

While many municipalities in Quebec are undertaking innovative MM initiatives,11 the focus of our research has been on provinces where there is a fundamental shift taking place – from exclusionary zoning to legalizing and promoting a greater diversity of housing.

Edmonton receives praise from many national housing advocates for its equity-based Infill Roadmap, being the first major in city in Canada to eliminate parking minimums, and for a commitment to a transparent and accountable approvals process. Kelowna is known for innovative needs assessments and being one of the first cities to develop replicable and rapidly approved MM designs. Kitchener has focused on affordable and nonmarket MM housing in proximity to its game-changing light rail transit network.

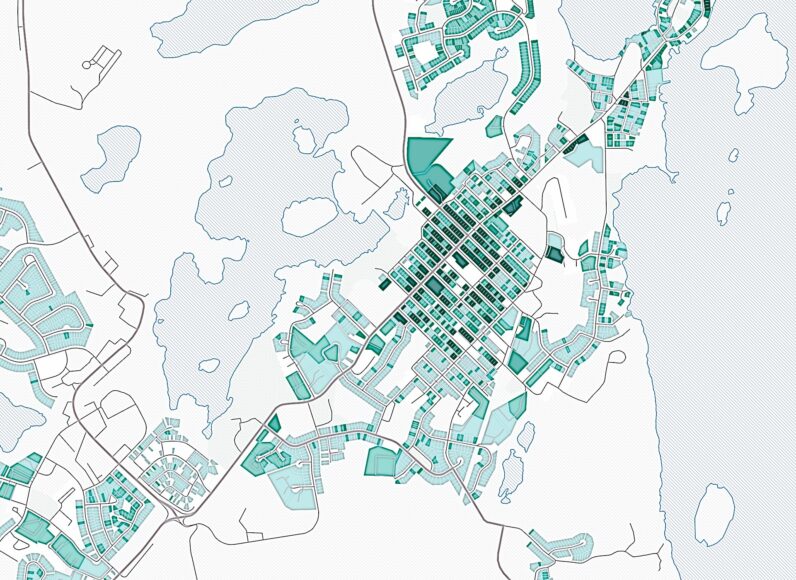

Edmonton

Since its 2010 City Plan, Edmonton has taken a gradualist approach to comprehensive planning reforms, within a strong set of equity-based housing targets and sub-targets. The city has a minimum density target of 45 units per hectare in new suburban growth areas as well as established neighbourhoods, encouraging ADUs and multiplexes in new subdivisions. It also has a target of 16% nonmarket (public, community, co-operative) housing in every neighbourhood. In 2015, garden and garage suites became legal as-of-right, and lot splitting was permitted. The 2018 comprehensive Infill Roadmap outlined a set of bold moves, and by 2023, Edmonton had greatly simplified its residential zones and design requirements.

The Infill Roadmap also included actions to improve consistency and speed for its development-permitting process. Edmonton has a newly-created Housing Action Team that brings together city finance, urban planning, and community services, including nonmarket housing and homelessness services.

Infill Development in Edmonton Association (IDEA) brings together SME infill developers who meet regularly with planning staff. We also spoke to a local councillor who had undertaken research on affordable ADUs. Edmonton also rolled out public education tools like videos, informative web pages, and exhibits to explain zoning and regulatory change processes.

Kelowna

Kelowna’s 2020-2040 Community Plan sets ambitious infill directions, such as creating vibrant city centres, focusing growth along transit corridors, and halting the planning of new suburban neighbourhoods. Much of Kelowna is now covered by four multi-unit zones. Most of the core area can have up to six ground-oriented residential units, and up to six storeys on transit-supportive corridors.

Kelowna, like Edmonton, maps infrastructure capacity for intensification and is working toward a much more transparent approvals-tracking process. Kelowna has identified hundreds of lots eligible for ‘fast-track’ approval in the core area. When combined with pre-approved designs, application for these lots can be approved within 10 business days. Also like Edmonton, municipal government is increasingly engaged in partnership development and civic learning, promoting a ‘Mddl school’ led by the Calgary-based development consultancy Mddl to increase understanding of replicable design, finance, and approvals enablers for scaled up MM.

Kitchener

Kitchener is one of few Ontario municipalities that has allowed duplexes citywide since the 1980s. Kitchener’s 2020 Housing for All strategy focuses on affordable MM enablers, including legalizing congregate housing, increasing the number of ADUs permitted on a lot, waiving application fees for affordable and nonmarket development, and enacting a rental replacement by-law to preserve affordable units.

The City has approved zoning changes to allow greater height and density around major transit station areas as-of-right than are required by the province. Like Edmonton and Kelowna, digitizing most elements of the approvals process has reduced approval times from an average of 17 to 5 months over the period 2019 to 2023.

Conclusion

Missing Middle is not a magic bullet. More well-located and suitably sized options for ownership and rental do not automatically translate to affordability, especially since senior governments seem reluctant to adequately subsidize housing. However, the kinds of supply unlocked by the reforms described above are essential for affordable, climate resilient, accessible, and healthy cities of the future.

The notion that zoning reform, however comprehensive, will likewise unlock well-located housing, ignores 50 years of increasing restrictions through building codes, design requirements, risk-averse financing, approval delays, and development taxes. To rapidly scale up MM, senior government housing targets and affordability and equity sub-targets are necessary, along with public education, nurturing a new generation of SME developers, and rolling back the toxic concepts of ‘growth paying for growth’ and homeowners being able to choose their neighbours. Low-income housing requires subsidies that are well beyond the capacity of local governments to pay. Similarly, infrastructure improvements in the face of climate change cannot be paid for by new residents.

Canada quickly needs to determine who needs what type of housing, where, and at what cost. Then it must ensure what housing policies at all three levels of government support these needs. Lessons from Canadian and international good practices suggest that MM reforms must be comprehensive, equity-focused, and integrated with long-term infrastructure planning to scale up affordable housing where it is most needed.