The following set of Housing Supply Mix Strategy briefs are based on research conducted by School of Cities and City Building TMU to inform the Task Force for Housing and Climate regarding Canada’s housing needs.

Quick links to the Supply Mix Strategies >>

As the 2020s unfold, Canada faces two challenges. First, the nationwide housing affordability crisis is growing, putting social and economic well-being in jeopardy for all Canadians. In 2022, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) recommended that 5.8 million new homes be built in Canada by 2030 as a strategy to restore housing affordability. However, this alone will not solve Canada’s housing affordability crisis.

Second, the threat of climate change continues to progress, putting pressure on the country to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as quickly as possible. A poll conducted by the Task Force for Housing and Climate found that more than 4 in 5 Canadians want new housing built to be resilient to the impacts of climate change, which shows that Canadians are alarmed about both the housing affordability crisis and the worsening climate crisis.

About this research

The Task Force for Housing and Climate consists of fifteen housing experts from across Canada; in March 2024, the Task Force released their Blueprint for More and Better Housing presenting recommendations for all levels of government on fixing Canada’s housing crisis in a climate safe way.

To understand how to best achieve the CMHC’s housing supply target while still meeting Canada’s climate and affordability goals, the Task Force commissioned experts to model GHG emissions scenarios based on where, what, and how 5.8 million new homes are built. As part of this project, the School of Cities and City Building TMU produced Targeting the Right New Housing Supply in Canada, a research report exploring what types of housing are needed and for whom to address affordability and location objectives.

This set of Supply Mix Strategy briefs are derived from this report and present key findings for the type of housing Canada needs, along with top recommendations by the Task Force that address the findings.

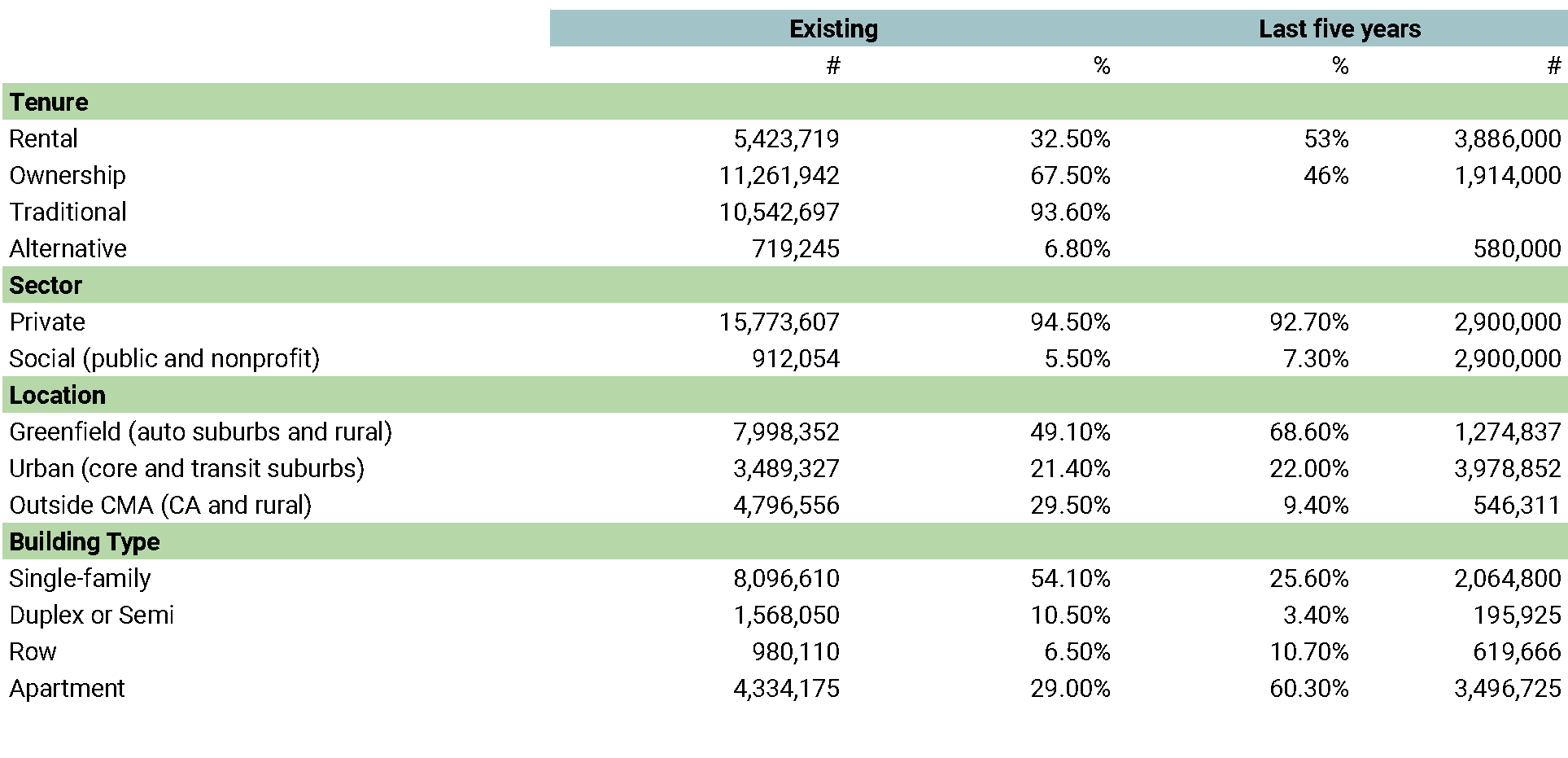

Existing housing mix in Canada

Aligning housing supply with affordability and climate goals

The CMHC’s 5.8 million homes target aims to not only build enough homes to meet the projected number of households by 2030, but also aspires to build an additional 3.5 million homes “beyond predicted growth in the number of households,” to restore affordability.1 Studies show that this process, known as filtering, can reduce prices by a few percentage points but won’t fill the structural gap between income and housing costs and takes too long to trickle down.2

- Its supply is disproportionately ownership (66%), when demand is overwhelmingly for rental housing. Most housing is built by the private sector, which is subject to speculation and financialization, at a time when many Canadians are experiencing poverty and financial insecurity.

- Almost 70% of housing is on greenfields (whether auto-oriented suburbs or exurban areas), when building in existing neighbourhoods results reduces both emissions and the costs of commutes. Just 29% of Canada’s housing units are in apartment buildings, despite the benefits of density for affordability and emissions reductions.

- 95% of Canada’s housing stock is built by the private market, with decades of disinvestment in non-market housing.

There are signs of improvement, but urban sprawl persists. Across three of these dimensions, Canada is trending in the right direction: we are building more rental, more social housing and significantly more apartment typologies. The biggest challenge remaining is building in existing urban and suburban lands, since a disproportionate share of construction continues to land outside our transit-oriented urban areas.

- Canada requires a robust Housing Needs Assessment

Achieving a green and affordable supply mix for all Canadians requires a more robust housing needs assessment beyond a numeric target, and a supply mix strategy to alleviate pressures on the current housing stock and construct new housing with both market and non-market options. Jurisdictions such as British Columbia are conducting these assessments.

- A supply mix assessment should identify and frontload the right housing that addresses both the affordability and climate crises with simultaneous effectiveness. Empirical evidence shows that building more market-rate supply will not filter to affordability in the near term, although it will alleviate pressure on older existing stock by accommodating market-rate household demand.(i)

- Not targeting the right supply misdirects scarce resources and infrastructure investment and can “bake in” decades of climate and affordability consequences while putting municipalities in financial risk.(ii) This will require new federal programs that specifically support social housing.

Supply Mix Strategy Briefs

1. Preservation

- The first step to solving the housing crisis is to preserve Canada’s affordable housing stock, which is being lost at an alarming rate.

2. Student Housing

- Purpose-Built Student Accommodation can provide secure rental for students and reduce pressure on private rental supply

3. Purpose-Built Rental Housing

- Canada must create an adequate and affordable supply of purpose-built rental apartment buildings to meet a growing demand for secure rental housing.

4. Non-Market Housing

- Canada needs at least 40 % of new housing to be outside the private market.

4a. Social Housing

- Canada has neglected to build social housing to meet the need and needs to at least double its stock

4b. Not-For-Profit and Co-op Housing

- Canada needs to rebuild and scale the NFP and Cooperative housing industry to meet the need for non-market housing.

5. Building In, Not Out

- Canada needs to curb urban sprawl development with an intensification-first strategy.

6. Middle Housing

- We need to build more in-between housing to provide family-friendly alternatives to sprawl housing

7. Recycled Houses

- We need better seniors’ housing to accommodate an ageing population and free up millions of detached houses for the younger generations.

1. CMHC, “Canada’s Housing Supply Shortages: Estimating what is needed to solve Canada’s housing affordability crisis by 2030,” (June, 2022), P. 6, https://assets.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/sites/cmhc/professional/housing-markets-data-and-research/housing-research/research-reports/2022/housing-shortages-canada-solving-affordability-crisis-en.pdf?rev=88308aef-f14a-4dbb-b692-6ebbddcd79a0&_gl=1*1k9jm8h*_ga*MjQyNjQyNjU5LjE3MDMwMDc3NzM.*_ga_CY7T7RT5C4*MTcxMDE3MjI1NS4yMC4xLjE3MTAxNzIyOTIuMjMuMC4w*_gcl_au*MTMyMDgzMjAxLjE3MDMwMDc3NzM

2. Stuart S. Rosenthal, “Are private markets and filtering a viable source of low-income housing? Estimates from a “repeat income” model,” American Economic Review, 2014, 104(2), 687–706, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.104.2.687 ; Jonathan Spader, “Has housing filtering stalled? Heterogeneous outcomes in the American Housing Survey, 1985–2021,” Housing Policy Debate, 2023, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2023.2298256

3. Douglas Porter and Robert Kavcic, “Catch-’23: Canada’s affordability conundrum,” BMO Economics, (2023, May 26), https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.104.2.687 ; Stuart S. Rosenthal, “Are private markets and filtering a viable source of low-income housing?…”

4. For example, The Ontario government changes legislation to access land in the Greenbelt driven by an indiscriminate housing supply target and without a comprehensive assessment.Municipal infrastructure costs without a demand needs assessment can result in financial risk to municipalities, See Hemson Consulting, “How Many Homes do we Need Build Faster? Review of Ontario’s 1.5 Million New Homes” Prepared for the Regional Planning Commissioners of Ontario, March 2023.; Bonnie Lysyk, “Special Report on Changes to the Greenbelt,” Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/specialreports/specialreports/Greenbelt_en.pdf ; David Thompson, “Suburban Sprawl: Exposing Hidden Costs, Identifying Innovation,” Sustainable Prosperity, (October 2013), https://institute.smartprosperity.ca/sites/default/files/sp_suburbansprawl_oct2013_opt.pdf

Location: Gordon et al., 2023, Canadian Suburbs Atlas. Data for existing is 2021 and last five years are 2016-2021. The Atlas uses journey-to-work mode choice to distinguish between auto-oriented and transit-oriented suburbs.

Building type: 2021 Census and Building Permit Survey, Stats Canada. Last five years are 2018-2022.

Sector: 2023 data. Last five years are 2019-23. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610068801&pickMembers%5B0%5D=8.20230401&pickMembers%5B1%5D=1.1&pickMembers%5B2%5D=2.1&pickMembers%5B3%5D=3.3&pickMembers%5B4%5D=6.1

Tenure: 2023 data. Last five years are 2019-23. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610068801&pickMembers%5B0%5D=8.20230401&pickMembers%5B1%5D=1.1&pickMembers%5B2%5D=2.1&pickMembers%5B3%5D=3.3&pickMembers%5B4%5D=6.2