The School of Cities’ Metropolitan Mindset initiative, led by Don Iveson, Canadian Urban Leader, and Prof. Gabriel Eidelman, aims to improve urban governance across Canada through research, education, partnerships, and advocacy.

In November 2023, the School released Toward the Metropolitan Mindset: A Playbook for Stronger Cities in Canada as a starting point for greater dialogue between governments, industry, civil society, and the public about the future of metropolitan governance in Canada.

In the spirit of mutual learning, debate, and appreciation of Canada’s distinct institutional traditions and metropolitan histories, the School has invited academic experts and policy leaders from across the country to respond to Iveson and Eidelman’s report and answer the question: “What are the prospects for cultivating a metropolitan mindset in the city-region(s) you know best?”

The following submission focuses on the Metro Vancouver area, authored by Dr. Alexandra Flynn, Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia’s Allard School of Law, and Fellow at the School of Cities’ Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance.

To read all the response papers, visit the Metropolitan Mindset website at metromindset.ca. To contribute your own response, please contact communication.sofc@utoronto.ca.

Cultivating a metropolitan mindset in the Metro Vancouver area: the tricky case of housing

Federal, provincial and municipal governments create and deliver policies and services, with leaders that are accountable to the public through regular elections. However, we must not lose sight of the regional level, too. As Iveson and Eidelman detail in Toward the Metropolitan Mindset, regions impact issues like transit, water, and especially, housing, whether they are formal governments, have delegated authority, or are acting as a diverse set of municipalities.

Experts have long observed that highly local decision-making means more exclusive, less equitable decisions. Basically, the smaller the geography, the more likely that narrow interests will be considered. One manifestation of this is ‘NIMBYism’ – or the pernicious problem of ‘not in my backyard’ thinking – where neighbourhood residents may oppose supportive or other forms of low-income housing. Thinking regionally – or as Iveson and Eidelman put it, adopting a metropolitan mindset – helps us to avoid siloed thinking of ‘wicked problems’.

I am writing this paper from the Metro Vancouver area, home to almost two dozen municipalities and multiple Indigenous communities, which together comprise a population of approximately 2.6 million people. This region is the epicentre of the housing crisis and is by any measure deeply unaffordable. In focusing on Metro Vancouver, I argue that cultivating a metropolitan mindset helps us to identify housing gaps. Without it, we fail to see the larger issues at stake.

Metro Vancouver’s housing crisis

As of 2023, the benchmark price for all residential properties in the Metro Vancouver region was $1,175,100. Housing sales in the region skyrocketed over a three-year period, rising 14.5% from June 2020. Data showed that these high levels of unaffordability had a direct impact on renters: Canada’s most expensive rental markets are also in the Metro Vancouver area, with average rents rising every year.

Two factors contribute to the concentration of Canada’s most expensive rental markets in Metro Vancouver.

- First, there is a rental rate gap between occupied and unoccupied units. A CMHC report from January 2023 on rental housing in Canada found that the asking rent for vacant units in Vancouver was, on average, 43% higher than the rates for occupied units. This is well above the annual rent increases allowed for occupied units, which were set at 2.5% in 2019, 2.6% in 2020, 0% in 2021 and 1.5% in 2022. Without vacancy controls in effect, landlords can raise rents to any level the market can bear.

- Second, there is limited purpose-built rental stock. In a 2021 report, the City of Vancouver estimated that 80% of purpose-built rental housing was built before the 1980s. In the early 1990’s, the federal government downloaded responsibility for housing to the provinces. In turn, the province looked to municipalities to build affordable housing for their constituents, without providing adequate funding, leading to little to no development of purpose-built rental stock in the last three decades. Macroeconomic changes also made purpose-built rental less viable as an investment. While the condo market and secondary suites have played an important role in meeting tenants needs, these markets are also more susceptible to short-term rentals and positioning as investment that contribute to their precarity.

The province is the government with the greatest legislative power to address these hefty issues. However, in doing so, regional data is crucial for knowing what kinds of tenancy protections to introduce, and what size and location of housing is needed.

Digging into the data

The Housing Assessment Resource Tools (HART) project, which runs out of UBC’s Allard School of Law and which I lead, used custom data from Statistics Canada to quantify housing need at municipal, regional, provincial, and federal levels. We also examined which populations were in most acute housing need. We broke populations into five income levels, as well as by household size, to show maximum affordable housing costs.

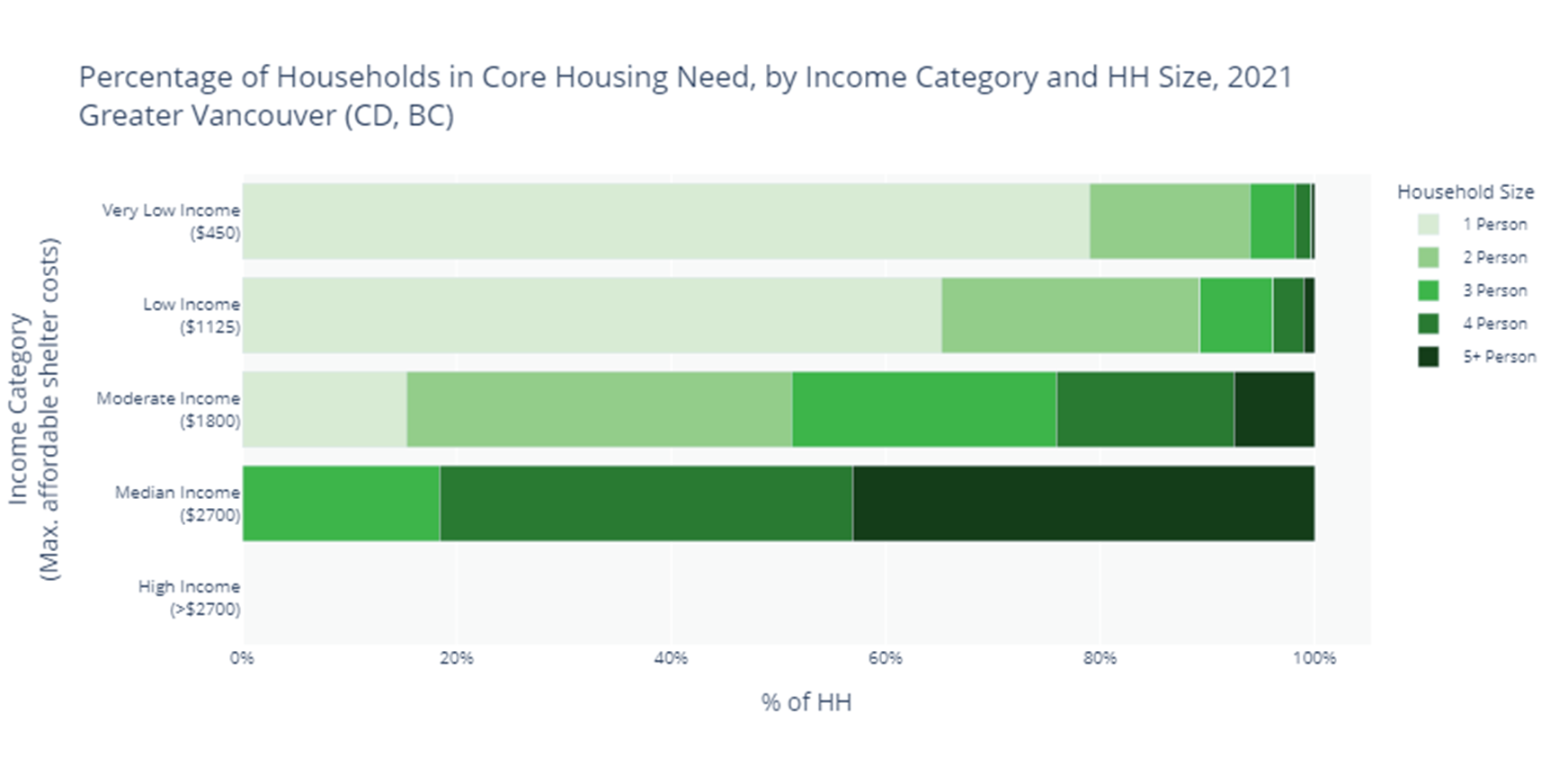

HART data show that the lack of affordability has hit lower income people the most. In Metro Vancouver, about 60% of low-income households are in core housing need (see Figure 1). A household is in core housing need if its housing does not meet one or more of the adequacy, suitability or affordability standards and it would not be possible for the household to find housing they could afford, which meet all their needs in their community. According to the 2021 Housing Assessment Resource Tool profile for Metro Vancouver, there is a deficit of approximately 166,105 housing units in the region, and more than 100,000 of those units require rents of $1,125/month or less.

Figure 2 shows the households in core housing need in the Metro Vancouver area. In nearly all municipalities, two-thirds of very low- and low-income households are single-person households. In addition, 30% of low-income households have two or more people, who could afford a maximum shelter cost of $1,125. This means that they must find a place to live that costs $1,125 and can adequately house more than one person, which is no easy task in the Metro Vancouver area. In 2021, the average rent in Metro Vancouver for a 1-bedroom was $1,434 and a 2-bedroom was $1,830.

It is important to note that the lack of affordable rental housing in the Metro Vancouver region has not impacted all renters equally. Among visible minority households, 17.94% are in core housing need. This represents a significant number of households given that 68.7% of the Metro Vancouver’s population identified as a visible minority according to 2021 census data.

The lack of affordable rental housing also intersects with gender, and immigration status in important ways, as both single-mother-led households and refugee claimants have high rates of core housing need in the Metro Vancouver region. Approximately 30.64% of single-mother led households and 25.81% of refugee claimant-led households in the Metro Vancouver region were in core housing need according to 2021 census data. These proportions are likely higher in 2024, because pandemic-related benefits reduced core housing need in the 2021 census.

A metropolitan mindset

The data above shows the challenge of affordable housing across the entire Metro Vancouver region – not just the City of Vancouver alone — particularly for those with lower incomes. As the following three examples show, adopting a metropolitan mindset adds important context as we drill deeper into the data, leading to a richer analysis of what solutions will best address the issue.

A metropolitan mindset must account for First Nations and Indigenous Peoples

Metro Vancouver is located on the lands of 10 First Nations and numerous urban Indigenous peoples. The HART team was met with data gaps that affected the ability to assess Indigenous housing need.

The Tsawwassen First Nation published a 2021 Housing Need Assessment Report showing acute housing need. Based on a survey of a selected sampling group, about 45% of respondents are renters, a lower rate than in Metro Vancouver. Of all respondents, about 4% self-reported household incomes below $10,000, about 16% self-reported household incomes between $10,001 and $25,000, and about 18% self-reported household incomes between $25,001 and $50,000. There is a significant number of young adults aged 29 years or younger, who are spending 30% or more of pre-tax income on shelter costs, followed by a smaller yet equally important share of adults aged 50+. About 45% qualify for affordable rental housing, with 10% who can afford monthly rents up to $375 per month, 35% who can afford between $450 to $800 per month, and 30% who can afford between $850 to $1,200 per month.

Thinking regionally reminds us that First Nations data is crucial in understanding housing need in the Metro Vancouver area. Without it, we are missing important information on what kind of housing is needed where.

A metropolitan mindset shows proportion and overall amount of housing need

In Metro Vancouver, over a quarter (27% or 99,160) of renter households are in core housing need. But these households are not spread evenly: White Rock has the highest percent of renter households in core housing need (37% or 1,310), followed by Langley (36% or 1,610), and West Vancouver (31% or 1,410).

When it comes to those who are very-low income, meaning that they can only afford $450 per month for shelter costs, a little under three-quarters (71%) of those in the Metro Vancouver region are in core housing need. However, in White Rock, almost all (94%) of very low-income households are in core housing need, followed by Coquitlam (85%), and North Vancouver (85%). These means that finding homes that can accommodate those with very low incomes is almost impossible in these communities.

It is therefore tempting to conclude that housing need for very low-income households is more acute in communities like White Rock, but these figures must be contextualized with data from within the region. In terms of the overall quantity of renters affected, the largest number of renter households in core housing need are in the City of Vancouver (39,650), followed by Surrey (14,955), and Burnaby (10,100). Simply looking at housing need percentages at the municipal level tells only part of the story.

A metropolitan mindset shows the housing needs of different priority populations

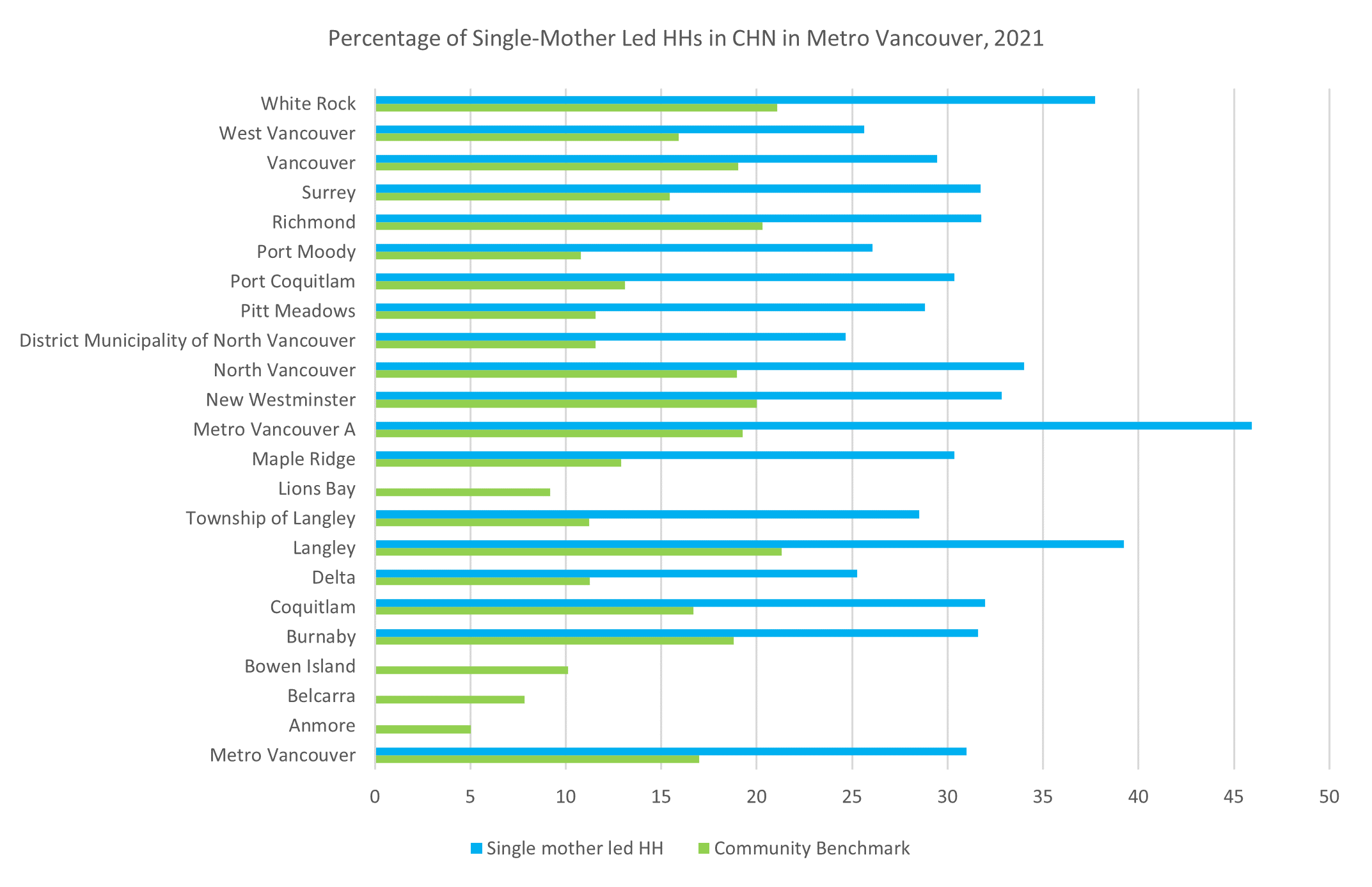

Another crucial issue is the housing need of vulnerable populations. In almost all municipalities, single mother-led households are most likely to be in core housing need out of all priority population groups (see Figure 3). In Metro Vancouver, almost one-third of single-mother led households are in core housing need, and in Langley, a little over 39% are in core housing need.

Other priority populations are differently represented across the region. Refugee-led households hold the highest rate of core housing need in North Vancouver (36%), New Westminster (35%), West Vancouver (31%), and the District Municipality of North Vancouver (28%), and second highest rate of core housing need in Burnaby (29%), Surrey (26%) and Delta (21%). Black-led households have the second highest rate of core housing need among priority populations in New Westminster (33%) and Port Moody (23%). Senior-led (85+) households have the second highest rate of core housing need in Langley (38%), White Rock (33%), and Port Coquitlam (26%). The Cities of Vancouver, Burnaby and New Westminster are the only Metro Vancouver cities where over a quarter of Indigenous households are in core housing need (27%, 25% and 25% respectively).

This data shows, first, that single mothers face significant housing needs across the Metro Vancouver area. It also shows that other priority populations face significant housing need, but that this need is not uniform across the regional area. Again, this data is useful in avoiding one-size-fits-all approaches to housing, while highlighting the common challenges faced by municipalities.

What does this mean?

A metropolitan mindset allows for more nuance in understanding the challenge of housing, especially for low- and very low-income households. It avoids the silos that result from looking at the issue at the municipal level, which doesn’t provide the big picture of housing need. Considering housing need at a regional level gives us greater clarity on where housing is needed and which populations need it.

In this paper I haven’t spoken about how this data can be mobilized regionally in terms of governance. However, Metro Vancouver is unique in Canada for having a robust regional body that allows for dialogue and coordination amongst municipalities (although only one of the ten First Nations). Perhaps this body can be leveraged in sharing information, building greater dialogue, avoiding conflict, and crafting solutions. Adopting regional thinking in housing may take time, but also holds great promise in addressing one of Canada’s most wicked problems.