This course was led by Professors Aditi Mehta and David Roberts of the Urban Studies program at the University of Toronto

Introduction

In 2023, wildfires ravaged Canada, burning more square-kilometers of land than ever recorded in the country’s history. The capital city of Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories facilitated an unprecedented evacuation of over 20,000 residents as forests blazed. Canadian cities such as Yellowknife must grapple with how to prepare, respond to, and recover from disasters while also prioritizing justice. With that said, what does it mean for a remote/rural city to be resilient to wildfires?

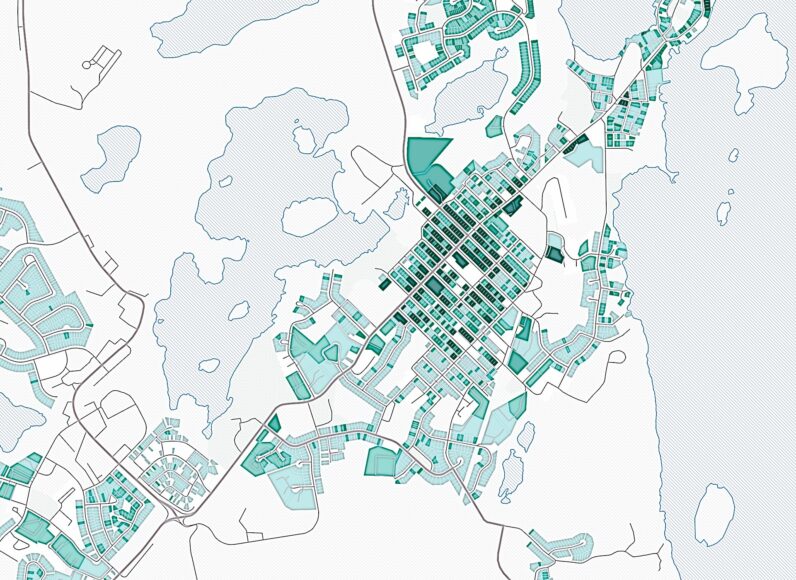

In this graduate summer field course, students visited Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories from June 23-28th, 2024 to explore this question in the context of housing policy and communication infrastructure. Through site visits, interviews, and focus groups with municipal and provincial officials, community-based organizations, residents, and indigenous leaders, students investigated how the housing crisis and climate change are intertwined, as well as explored how to build more resilient communication infrastructure in Yellowknife.

Check out the class blog below to learn more about the class experience and research.

Students learned about and further researched a range of policy topics related to disaster response and resilience with regard to housing and communication in Yellowknife. The final policy white papers explored non-profit collaboration, FireSmart programs, the uses of forestry biomass for climate change adaptation, fire preparedness in urban design, and mental health supports post-disaster. You can read their final papers here and meet the class below!

- Environmental justice and wildfire evacuations: the case for nonprofit collaboration among homeless-serving organizations in Yellowknife, NWT by Lilian Dart

- Igniting Safety: Integrating Fire Preparedness into Yellowknife Developments by Ashwini Gadtoula and Roya Asgharzadeh

- Yellowknife, a FireSmart city by Léo Jourdan

- Addressing Mental Health Needs Post Evacuation in Yellowknife by Ava McKay

- The Potential of Transforming Forestry Biomass from Firebreaks in Yellowknife into Sustainable Value-added Products: Biopolymer, Syngas and Biochar by Esther Tang

- Long-term human recovery to better prepare for the future by Amélie Zarir

By Lilian Dart and Ava MacKay

Our first official research day in Yellowknife. While we had been reading media and academic articles about the Canadian north as well as discussing climate resilience and housing as a class, we were excited to be able to learn firsthand experiences of the wildfires and systems planning. We had an action-packed week planned, with over 12 official interviews plus countless informal conversations with Yellowknife residents at restaurants, in office buildings, and in parks across the city. On Day 1, we met with city staff, elected officials, and NGOs and learned about emergency preparedness, community resilience, leadership and communication, and taking care of vulnerable people during crises.

9:00 am: Meeting with Craig MacLean

Photo credit: Ava MacKay

Our first meeting of the week took place at Yellowknife City Hall with Craig MacLean, the Director of Public Safety for the City of Yellowknife. In his role, Craig is responsible for the fire division, municipal enforcement, parking services, and traffic control. Before our visit, we had been researching the 2023 wildfires and trying to understand the procedures that led to the eventual evacuation. Our conversation with Craig was crucial for gaining a comprehensive understanding of last year’s events and the city’s role in the evacuation.

Craig shared that his first goal in his current role was to restructure the fire division and the emergency management program. He felt that there had been a lack of emergency preparedness within the organization for about 20 years, which he attributed to the busyness of Yellowknife. During last year’s wildfire season, Craig served as the Planning Section Chief under the city’s Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) model. Much of his work until the territory declared a state of emergency involved developing fuel breaks on the city’s perimeter and planning protection lines around the city. Almost immediately following the evacuation, he said they started work on a re-entry plan for when people could return. Craig said some of the main challenges during this time were managing businesses and people who stayed behind, assisting those who left their pets behind, and coordinating volunteers.

Reflecting on the evacuation, Craig shared that the city had never considered evacuating in their emergency management plan. He mentioned how the city’s plan was based on moving high-risk areas into designed safe zones in the urban core. Although the city has a suitable facility, he said they lacked the necessary health and social service resources. Further, the city was already hosting other communities that had been evacuated, so the territory made the decision to evacuate Yellowknife based upon resource availability. The territory called the evacuation because they had jurisdiction as the fires were outside of the municipal boundary. The city is currently collaborating with the territory to update and align their emergency models. This year, the city is focusing on training and educating team members, improving communication with vulnerable populations, and making adjustments to the forest and fuels in the Boreal Forest surrounding the city.

While wildfires are natural to the north and to the Boreal Forest, the fires last year were historically the most severe they have seen in the territory. Because of this, Craig said wildfires are at the top of people’s minds and cause anxiety; the city is looking at ways to involve communities in wildfire protection plans. The city is looking into incorporating FireSmart principles to support the goals of its Community Wildfire Protection Plan, hoping for greater resident involvement in protecting the city from wildfires. The FireSmart program is a national initiative aimed at minimizing the impacts of wildfires and enhancing neighbourhood resiliency. This idea is echoed in the recommendations made by Dodd et al., in their study about the 2014 wildfire season in the Northwest Territories. In their study, they highlight the importance of motivating community members to engage in fire mitigation efforts and speak to community-based adaption and education initiative.

Craig shared his honest thoughts on the evacuation process and areas for improvement in the future. It was clear from our conversation that planning and executing evacuations can be challenging, but how incorporating the lessons learned from last year into future planning is a top priority for Craig. Léo Jourdan reflected on his interview with Craig, saying, “Our first meeting with Craig was a strong start to the week! I came into it with preconceived ideas on wildfire prevention practices in Yellowknife, but our conversation with him really helped me understand what was and wasn’t happening.”

10:00 am: Meeting with Rebecca Alty

Next, we met with Mayor Rebecca Alty, who invited our class to Yellowknife and was eager to have student researchers studying the evacuation response. Mayor Alty exuded a strong and approachable presence as she introduced herself to the class, explaining that she got into politics to “give back to the community”. While we had just been briefed about emergency procedures from Craig, Mayor Alty gave us the perspective of an elected official – namely, the leader that people look to when they are facing uncertainty.

Mayor Alty has been the leader in her community through two emergencies: Covid-19 and the 2023 wildfires. Throughout our interview, she highlighted how these emergencies were similar in both the leadership strategy and the response of the public. The emotions of the public are parabolic, she said – that is, the original panic is replaced by care and strength which is replaced by anger and frustration. As the leader, Mayor Alty said that a regular drumbeat of communications is integral for “killing the rumour mill” and for easing uncertainty. However, she highlighted the difficult balance of relaying information – communication without alarmism that could cause further distress.

To ensure that residents who evacuated were able to receive communications from Yellowknife, the city hosted a daily live streamed media briefing led by Mayor Alty. She took every opportunity to speak to the media, but prioritized local and regional media to ensure that the message was getting to those affected the most by the evacuations. While Mayor Alty underscored how evacuation planning could be improved, she expressed her gratitude to be in this role as it is “closest to the people”. Throughout the interview, we were enamoured by Mayor Alty’s calm, confident, approachable, and reflective nature, and our class agreed that Mayor Alty was the kind of leader that you would want in charge during an emergency. Student Roya Asgharzadeh spoke to this approachability saying, “An observation I think many of us made early on is just how local and accessible decision makers like the mayor are in the city.” She added, “It reminds us that the people we’ve been meeting are not just their titles, like “mayor” or “director”, but are also members of the community.”

1:30 pm: Meeting with Dan Ritchie

After a quick lunch at a busy Vietnamese restaurant, we met with Homelessness Specialist for the City, Dan Ritchie. Although all of Canada is experiencing a housing crisis, we learned through class readings that Yellowknife’s context exacerbates the issue due to the limited rental opportunities and high construction costs for the transportation of building materials and labour. We also learned that people experiencing homelessness are particularly vulnerable to wildfire evacuations due to lack of resources and social supports. Our class was keen to speak to Dan, seeking his insights into the evacuation planning for people experiencing homelessness and the impact of the temporary location.

We heard that many people experiencing homelessness were “lost in the system” due to the lack of a cohesive plan. Dan actually began in his role in September after the 2023 wildfires, soon after the evacuees arrived back to Yellowknife. We learned that his role was vacant for the six months leading up to the evacuation, and discussed how this might have been part of the problem in lack of coordination. Dan explained the role of the city in addressing homelessness, which is largely to distribute federal funding to local homeless-serving agencies. However, he seemed hopeful that his role in the city’s Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) could have a positive impact on coordination of services, connecting service providers, and in relationship building. Dan underscored how the fragmented response led to people falling through the cracks, but further looked ahead to improved data quality, the emergence of conversations like the roundtable on homelessness, and increased collaboration partner service organizations which could lead to a better and more organized response in the future.

3:30 pm: Meeting with Tammy Roberts

Next, we made our way to Home Base to connect with Tammy Roberts, the organization’s executive director. Home Base is an organization in Yellowknife that offers support and housing to local vulnerable youth. Previous discussions with city officials praised Home Base for successfully handling an evacuation situation. Naturally, we were eager to hear about the evacuation and to meet Tammy, who had been in a leadership position at the time. During our meeting, we discovered that Home Base had initiated their evacuation prior to the official order and had an evacuation committee that had been planning for a potential evacuation for some time. They started planning and preparing early so that time was on their side when the evacuation order was eventually announced.

For the home base team, managing the evacuation impact through planning was of the utmost importance. Tammy shared how many of the youth they service have already been displaced due to experiences in the foster care system, and Home Base wanted to reduce the impact of the evacuation as best as possible. Part of this meant communicating with the youth about their plan every step of the way and providing as much support from staff as possible.

Home Base took the youth to a small oil and gas work camp in Zama City, Alberta, where they provided various programs to meet the needs of the youth. Tammy outlined all the ways they ensured the safety of the youth, maintained a sense of community, and got creative with keeping the youth engaged and entertained. Tammy remembered how they gave the young people an allowance and created a small store where they could purchase snacks and supplies. The youth also took turns walking the dogs at the camp and even assisted someone in practicing for their driving test. During the last two weeks, three elders and two counsellors joined the camp to support and share knowledge with the youth. Despite the severity of the situation and the potential safety risk of evacuating youth with high needs, Tammy laughed as she reminisced about the positive memories during the evacuation.

Despite these positive memories, Tammy shared that returning home was difficult, as she felt the youth lost the constant support and guidance provided at the camp. In addition, back in Yellowknife, some of the youth ceased utilizing services, and Home Base saw an increase in addiction issues. She said that some youths asked to return back to the camp or asked to bring some of the elements of camp back to Yellowknife. So, after the evacuation, Home Base incorporated successful aspects of the camp, such as movie nights and dog walking, into their daily operations and altered evacuation plans based on lessons learned.

Some of our key takeaways from this interview were the importance of creativity and out-of-the-box thinking, maximizing support to ensure safety, and the importance of creating a sense of community. After our time with Tammy, we were left blown away by her openness, steadfastness, warmth, and strength. Classmate Ashwini Gadtoula reflected, “Tammy had such an inspiring story; her perspective on working in a silo in a time of crisis was interesting!”.

Home Base took the youth to a small oil and gas work camp in Zama City, Alberta, where they provided various programs to meet the needs of the youth. Tammy outlined all the ways they ensured the safety of the youth, maintained a sense of community, and got creative with keeping the youth engaged and entertained. Tammy remembered how they gave the young people an allowance and created a small store where they could purchase snacks and supplies. The youth also took turns walking the dogs at the camp and even assisted someone in practicing for their driving test. During the last two weeks, three elders and two counsellors joined the camp to support and share knowledge with the youth. Despite the severity of the situation and the potential safety risk of evacuating youth with high needs, Tammy laughed as she reminisced about the positive memories during the evacuation.

Despite these positive memories, Tammy shared that returning home was difficult, as she felt the youth lost the constant support and guidance provided at the camp. In addition, back in Yellowknife, some of the youth ceased utilizing services, and Home Base saw an increase in addiction issues. She said that some youths asked to return back to the camp or asked to bring some of the elements of camp back to Yellowknife. So, after the evacuation, Home Base incorporated successful aspects of the camp, such as movie nights and dog walking, into their daily operations and altered evacuation plans based on lessons learned.

Some of our key takeaways from this interview were the importance of creativity and out-of-the-box thinking, maximizing support to ensure safety, and the importance of creating a sense of community. After our time with Tammy, we were left blown away by her openness, steadfastness, warmth, and strength. Classmate Ashwini Gadtoula reflected, “Tammy had such an inspiring story; her perspective on working in a silo in a time of crisis was interesting!”.

5:00 pm: Dinner with Mayor Alty at Zehabesha Traditional Ethiopian Restaurant

We were invited to dine at Zehabesha Traditional Ethiopian Restaurant with Mayor Alty. It was a great end to our first day and an opportunity to speak more with an elected official.

7:00 pm: Watch the Stanley Cup game in Oilers territory.

To end a busy first day, some of the class watched the Stanley Cup playoff game at a restaurant. Because of the close proximity to Edmonton, Yellowknife has many oilers fans!

Conclusion

We had a packed schedule on our first day in Yellowknife. But fuelled by amazing food and the midnight sun, everyone was feeling energized for the week to come! We ended the day eager to learn more from community leaders about their experiences and perspectives on the wildfire evacuations. Our conversations with Craig, Rebecca, Dan, and Tammy not only provided a window into the events of last summer, but also gave us a better understanding of the city of Yellowknife and the sense of community spirit.

By Amélie Zarir and Ryan Grover

We are delighted to be today’s bloggers, and to share with you the activities and reflections that took place. Amélie will be starting a PhD in Anthropology at the University of Toronto next September, and Ryan is a student in the Masters of Landscape Architecture program at the University of Toronto. We are both keen to learn from the people of Yellowknife and listen to their experiences with the wildfires.

Tuesdays Agenda: Tour of Old Town, lunch at Bullocks Bistro, discussions with Emily King and Kieron Testart, and the Yellowknife Farmers Market!

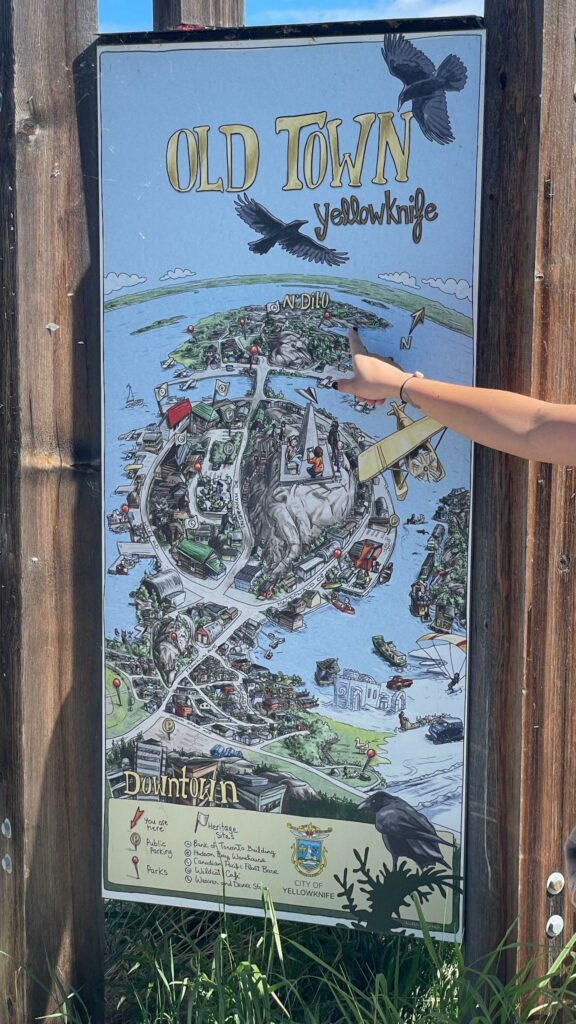

Tour of Old Town

This morning, our group had the opportunity to visit Yellowknife’s Old Town through a tour offered by Sundog Adventures. After meeting at Sundog Trading Post, our guide led us through various historical spots and tourist attractions, starting with our climb up “The Rock” to visit The Bush Pilot Monument. The monument sits atop this six-storey rock hill in the center of Old Town, overlooking Great Slave Lake and Back Bay. The monolithic monument stands in commemoration of the bush pilots of the 1920s and 1930s, who endured dangerous occupational conditions in furthering the development of the nation of Canada; ferrying passengers and mail, as well as mapping the land, and helping to grow the economy of the North.

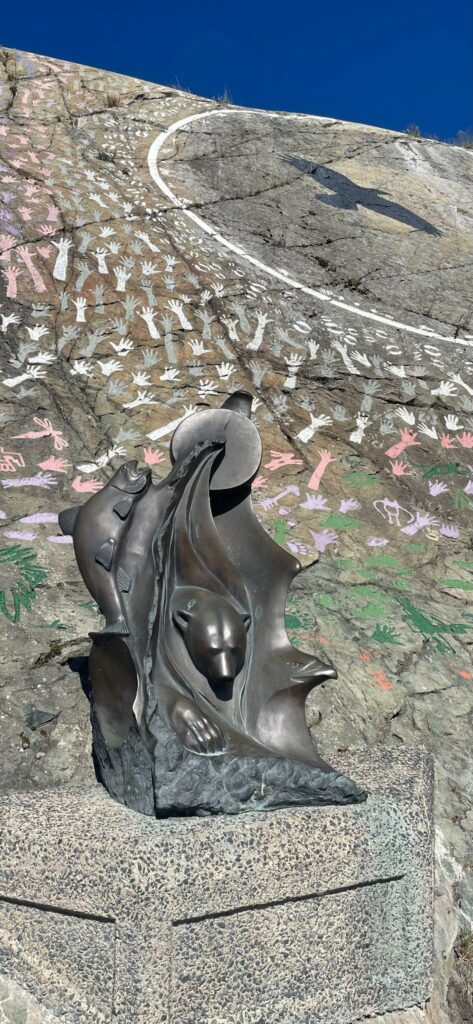

From “The Rock”, we walked down to the Yellowknife Cultural Crossroads, a monument in its own right. “The site is a testament to the close collaboration among Métis, Dene, Inuvialuit, English Canadian, French Canadian and Québec cultures and is dedicated to all peoples of the North,” reads the plaque embedded in the stone in both English and French. “The Power of Working Together” is engraved into the rock beside the plaque, using each of the eleven official languages of the Northwest Territories and symbols and imagery from the Métis, the Inuvialuit, and the Dene.

The sculpture is a collaborative piece between Sonny McDonald, a Métis from Fort Smith; John Sabourin, a Dene from Fort Simpson; and Eli Nasogaluak, an Inuvialuit from Tuktoyaktuk. The artists carved the sculpture from a block of marble formed on the shore of Great Slave Lake 2.5 – 4 billion years ago. The original marble sculpture is housed in the Legislative Assembly, while the bronze replica remains on site. This monument was full of life and exuded a sense of togetherness which we have seen reflected in the communities we came here to better understand.

On the way to Rotary Centennial Park Trail, we walked along Yellowknife’s most well-known street: Ragged Ass Road! The gravel road “was named by a couple of drunken prospectors who, despite relentless work, found themselves ‘ragged ass’ poor”. Many of the houses on this road have embraced the beloved namesake and history of their neighbourhood, embellishing their homes with various signs and decorations that really contribute to the sense of place that permeates throughout Yellowknife. Wandering the historic streets of uptown, this sense of place was really highlighted for us. Here is a selection of photos of just a few of the sights to be seen on a beautiful Tuesday in Old Town.

We finished our walk through Yellowknife’s Old Town by heading for the Bullocks Bistro. We shared a delicious meal based on a variety of local caught fish from Great Slave Lake such as Whitefish, Lake Trout, Pickerel, Great Slave Cod, or Arctic Char. Bullocks was voted the best fish and chips in Canada by Reader’s Digest magazine, and it surely lived up to its reputation! The restaurant itself was lovingly decorated by patrons from across the world, as people have covered nearly every available surface with signatures, business cards, and bank notes.

Discussion with Emily King

After lunch, we had the opportunity to lead the interview with Emily King. Emily King has been the GNWT’s director of Public Safety at the Emergency Management division since March 2022 . She has been working with the Emergency Management Organization (EMO’s) for 14 years now, having held various positions including Head of the EMO (2019-2022), strategic initiatives coordinator (2018-2019), and emergency management officer (2011-2018).

This meeting gave us an initial perspective on wildfire governance from the territorial perspective. During the interview, Emily explained how EMO’s work, sharing her feelings with us about some “misconceptions” surrounding GNWT’s role in emergencies. Five regional EMO’s are spread across the N.W.T. and their role is to support communities when they need resources. However, when the regional EMO is lacking resources, then the territorial EMO steps in to provide support. According to Emily King, their role is to provide aid in times of crisis when the community governments are exhausted (Blake in CABIN radio, 2024).

Emergency management in the N.W.T. is based on four pillars: prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery, all outlined within the Northwest Territories Emergency Plan. Since emergency management is based on risk analysis, we were led to question what constitutes a risky situation. Indeed, a situation perceived as risky by GNWT, such as the 2023 wildfires, in the end, was not for some individuals. For instance, some individuals did not view last year’s fires as an immediate threat necessitating evacuation. One member of the Dene Nation, for example, chose to stay behind to mark and control the fires.

In addition, the application of the emergency plan during the 2023 wildfires identified a number of challenges. According to Emily, the main challenges lie in the lack of communication between the various players involved and between bodies at different levels of government. This lack of clarity can also be applied to the roles and responsibilities within N.W.T and external to N.W.T. that were not clear. However, she said that her team was very clear throughout the evacuation regarding the evacuation guidelines. Similar to how municipal officials mention a lack of clarity, there seems to be a disconnect in understanding and communication between various levels of government. Emily King added that, in general, the huge lack of resources in staff, food, places to sleep, etc., are important issues to consider when thinking about evacuation.

Finally, despite all these challenges, Emily King considers the 2023 evacuation successful on the grounds that there was no loss of life and no damage to structures. The criteria used to ensure the success or failure of the evacuation is, in our view, an interesting avenue to explore, and may not be the same for everyone. “But of course, everyone has their own perspective, for sure” – says Emily King. She emphasizes that her opinion is personal and acknowledges that, for other members, the 2023 evacuation was not considered a success. It all depends on one’s perspective.

Discussion with Kieron Testart

After our meeting with Emily, we headed over to the Government of the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly to meet with MLA Kieron Testart. Kieron was the Director of Economic Development for the Yellowknives Dene First Nation during the 2023 wildfires and is a current Member of the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly. This meeting provided us with further insights on the response to the 2023 wildfires at the Territorial level of government. Our classmates Léo and Esther lead the discussion with Mr. Testart, where he outlined his experience as someone who stayed behind in Yellowknife during the evacuation last August. He found the evacuation process and overall response to the wildfire risk to be disorganized, exaggerated by the fact that there was no official chain of command regarding the jurisdictional authority between the various levels of government and in coordination with the Yellowknives Dene First Nation. This foundation of miscommunication led to a lot of confusion in the days leading up to evacuation, and people were receiving contradictory statements.

Kieron emphasized the work of the resident volunteers of Yellowknife, who stayed behind to help coordinate the evacuation and return. There was a team of 12 to work on the fuel breaks and another team of 30 who stayed to care for the animals and people who stayed behind. Kieron also shared his knowledge on some of the experiences of residents, and how they varied depending on what communities they were a part of and where they went. Upon return, Kieron had wanted to celebrate the incredible and brave work that the volunteers were a part of and have a community-wide appreciation event. However, due to the threat of wildfire smoke and the fact that not everyone was returning at the same time, the celebration was never held. Masters of City Planning student, Ashwini said “It was sad to hear that Kieron’s efforts to recognize the help of all the volunteers did not come to fruition. It made sense to hear that they felt rather abandoned after the fact.”

Kieron offered some next steps in response to the After Action Assessment being released by KPMG later this month. He suggests that the report must be implemented through policy and across the various levels of government so that if/when the City needs to respond to wildfire threats, each system of government has clearly defined jurisdictional authority. After our meeting, Kieron and his assistant Taylor took us on a tour of the building where we got to see the Council Chambers, the Caucus Room with paintings by A.Y. Jackson of the Group of Seven, and various pieces of historic Government objects such as the Mace, previous Speakers robes, and the former Speakers chair which was built to travel across the territory before having a dedicated building.

Yellowknife Farmers Market

We ended our exciting day with a visit to the 2024 Yellowknife farmers market located at the Sombe K’e Civic Plaza outside the City Hall. This market takes place every Tuesday during the summer (from June 4 until September 10), and provides space for 45 initiatives to present their products to the public. Despite the rain, our early arrival enabled us to see local businesses, farmers, food stands, and craftsmen setting up their booths. The ambient noises, the different smells, both spicy and sweet, reminded us of the lively neighbourhood life that brings people together. It was a colourful sensory awakening!

One of the highlights of the farmers market was visiting Mayor Alty at the City Hall booth, where she had information available for the community on fire safety preparedness as well as a raffle to win some sweet emergency kits! It was cool to see Mayor Alty in action, engaging with all members of the community. Our classmate Lily said, “the farmers market was truly a testament to a close knit community supporting each other! The councillors and mayor being so accessible and promoting their booth also added further efforts to communicate fire safety to the residents.”

We ended our exciting day with a visit to the 2024 Yellowknife farmers market located at the Sombe K’e Civic Plaza outside the City Hall. This market takes place every Tuesday during the summer (from June 4 until September 10), and provides space for 45 initiatives to present their products to the public. Despite the rain, our early arrival enabled us to see local businesses, farmers, food stands, and craftsmen setting up their booths. The ambient noises, the different smells, both spicy and sweet, reminded us of the lively neighbourhood life that brings people together. It was a colourful sensory awakening!

One of the highlights of the farmers market was visiting Mayor Alty at the City Hall booth, where she had information available for the community on fire safety preparedness as well as a raffle to win some sweet emergency kits! It was cool to see Mayor Alty in action, engaging with all members of the community. Our classmate Lily said, “the farmers market was truly a testament to a close knit community supporting each other! The councillors and mayor being so accessible and promoting their booth also added further efforts to communicate fire safety to the residents.”

By Roya Asgharzadeh and Claire Posno

Wednesday began in front of the hotel polar bear—our mascot rather than a threat. We discussed eight projects, sharing updates on policy dilemmas, research questions, roadblocks and future directions. The presentations covered fascinating interdisciplinary topics. For example, Ava is recommending a policy to commemorate volunteers, evacuees and service providers for their efforts in wildfire evacuations, acknowledging all experiences and emotions upon arrival to the territory. Léo is proposing that the territory strengthen their FireSmart initiative to empower homeowners and tenants to mitigate wildfires. Ashwini and Roya are drawing on their planning studies to envision a site-specific building that leverages community planning and wildfire-resistant materials.

Our discussion referenced Fainstein’s (2015) essay on resilience and justice, offering recommendations for fairer planning in response to disasters like wildfires. Specifically, just outcomes are more realistic if the most vulnerable communities are considered in the planning, prevention and recovery stages of disastrous events. When participants from lower socioeconomic communities participate and are promised financial resources, then better outcomes for rebuilding a city will result due to communities being able to move together amid change. However, making empty promises about financial support and/or participation is cautioned against, explains Fainstein (2015), because it could leave “poor residents with even fewer options than formerly” (p. 165). Our class honoured this perspective by considering populations and themes historically ignored in planning policies, such as mental health, Indigenous traditional knowledge, homelessness and renters. It was motivating to be part of these meaningful discussions and to anticipate everyone’s progress!

Visiting Dechinta

In the afternoon, we took a 25-minute bus ride from Yellowknife to visit the Dechinta Centre for Research and Learning. Dechinta, led by northern experts, teaches Indigenous land-based education, research and community programs rooted in Northern Indigenous knowledge and values.

Upon arrival at the homelands of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation, we walked 15 minutes down a rocky path and were welcomed by elders, researchers and community individuals. At a table, everyone introduced themselves, which led to a conversation about the 2023 wildfire evacuation and its impact on Dene ways of knowing and understanding. For instance, a newborn passed away last summer, likely due to thick wildfire smoke, and fewer caribou now travel to Dene land because wildfires outside the city’s focus have driven them further north.

Ryan reflected, “learning about the changing grazing patterns of the caribou was eye opening. The impact this has on the Dene community is significant and I look forward to expanding my perspective on such issues in my final project with Claire about the Dene Nation’s right to self-determination in wildfire communication.”

Listening to those at Dechinta and others who are not affiliated with the government, like service providers, revealed the community strength, organization and self-sufficiency in adapting to the lack of communication infrastructure during the 2023 wildfire evacuations. The land-based community at Dechinta and the surrounding Dene First Nation land provided some comfort by assigning roles and responsibilities when the Territorial Government lacked communication strategies, like coordinated evacuation notices and reliable helplines for information. This aligns with Hellenback et al.’s (2016) argument about the relevance and importance of Indigenous knowledge and practices in present-day scenarios, such as wildfires.

After our conversation we walked around the beautiful landscape. It was magical to smell the smoke escaping a canvas tent where Thumlee, a land-based educator and traditional knowledge holder, was tanning the hide to her desired colour. We then walked on smooth rocks to the water’s edge to observe the low water levels. As our visit came to a close, we headed back on the path and toured the rest of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation Land. The bus ride back to the city was filled with gratitude and reflection.

Roundtable on Homelessness

In the evening, we attended the Roundtable on Homelessness (see this Cabin Radio and CBC article). It was nice to see familiar faces from our interviews earlier in the week, but personally there was also a sense of guilt for participating. At first, we all sat in the back of the room so that we could just observe and listen. However, the event was structured for small breakout group discussions, so we were later split into smaller groups with other Yellowknife attendees. Having spent less than a week in the city, how could we comment on the current and future state while those actively experiencing homelessness weren’t even in the room? Coming from Toronto, conversations around homelessness are not new. While Yellowknife shares similarities with Toronto as they’re both urban centres, it faces unique challenges and circumstances.

Before coming to Yellowknife, we read Julia Christensen’s work on the state of homelessness in the North. One takeaway was the overrepresentation of homeless Indigenous people (Christensen et al., 2023). While it was great to have different levels of government, NGOs, and the public together, it quickly became apparent who wasn’t in the room. Indigenous people, especially those with lived experience, were noticeably absent. Georgina Franki, an activist in the city, spoke up about this discrepancy and how this environment can be intimidating, pushing the Indigenous homeless population out of spaces and discussions meant to be “collaborative”. In fact, before entering the building, someone outside was urging attendees to speak up for Indigenous people at the roundtable.

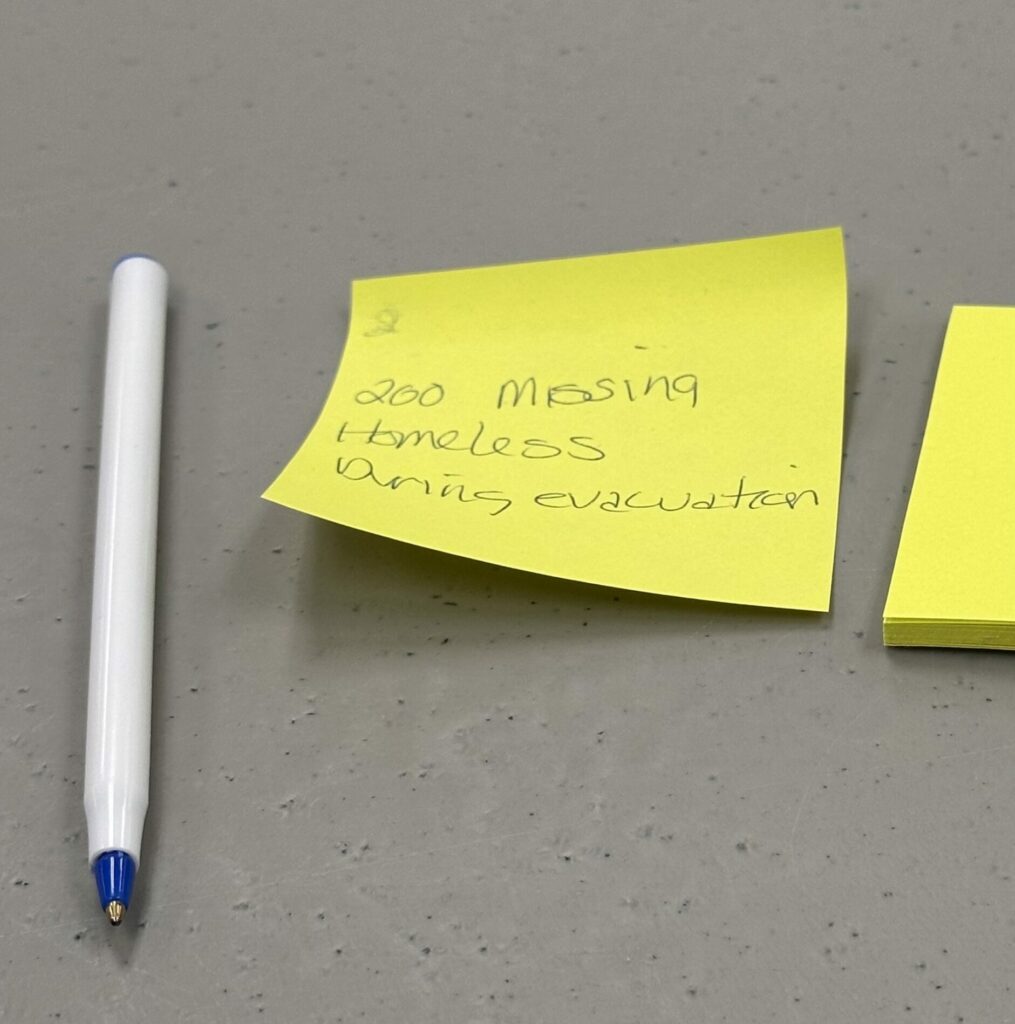

Franki also went around to each table and put down these sticky notes to highlight the fact that there are still 200 missing homeless people as a result of the evacuation. While the city starts to hold these important conversations on the current and future state of homelessness and emergency response, this served as a reality check to remind us of the vulnerable members of the community who have been overlooked, not just those absent from the roundtable tonight but those who haven’t returned to the territory as well.

Tina Wrigley (who sat at a table with Ava, Ashwini and Roya) spoke about the need to let Indigenous people help each other, especially when addressing mental illness and healing from trauma as a preventative measure to end the cycle. As Christensen points out, there are patterned ways of homelessness and more importantly how this cycle of Indigenous homelessness is “reproduced through culturally inappropriate social policy” (2023, p 20). This roundtable is supposed to be a kickoff to future engagement with the community, but there’s still a lingering sense of inaction if nothing changes.

Another common theme: the word crisis—people constantly repeating that the city is experiencing a homelessness crisis but not treating it as one. The government has all kinds of documents, like their 10-Year Plan to End Homelessness, but we have to question their efficacy in facilitating action. What progress has been made since its inception? In the context of wildfires and the reports of people outside of Yellowknife coming into the city after the evacuation, what has changed? How do these evolving circumstances factor into existing plans or have they become outdated? With the winter months approaching, this is a matter of life or death.

After conversations with classmates, the reactions of the people in the crowd were what stood out the most. While everyone in the room shared the same goal, there’s disagreements on how to reach it. Lily summed up some of these thoughts perfectly. She said “Participating in the roundtable was an invaluable experience for our class.The room was filled with people eager to work towards solutions for Yellowknife’s housing crisis – but, notably was missing people with lived experience with homelessness.”

There isn’t a singular path to end homelessness; what’s needed is a variety of coordinated efforts. Involvement from all levels of government, but most importantly, better representation of Indigenous people with lived experience can lead to better outcomes. Whether that be through removing barriers to certain positions or simply creating an environment that allows for more diversity in the room, clearly something needs to change.

Conclusion

Unlike the past two days, today’s meetings weren’t revolved around the questions we had coming into the city. Instead, the day involved a lot of listening and learning from each other and the great people we’ve been meeting through this course. Schedule-wise, this was one of our calmer days with only three scheduled meetings, but it left a deep impression for us to reflect on.

Hello everyone! I am Aditi Mehta, and have been an Assistant Professor of Urban Studies here at U of T since 2018. Prior to that, I completed my Masters and PhD in Urban Studies and Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. My research explores how people produce and disseminate knowledge about climate change, environmental disasters, and public health through new media tools to influence environmental policy in their neighborhoods either through meaningful public participation with local officials or via activism by organizing amongst themselves. I have anchored this interest in a variety of contexts including: 1) Toronto’s Regent Park, a rapidly gentrifying neighbourhood where a local non-profit is teaching residents how to produce media about their lived experience; 2) post-Katrina New Orleans and post-Sandy New York City, where residents used tech tools to combat harmful, dominant post-disaster narratives; and 3) prisons, which suffer from a variety of environmental justice issues and where access to new technology and information is limited. From 2016-2018, I investigated how federal and local affordable housing programs in the U.S. can help low-income residents better prepare for and recover from disasters. I have never been to the Canadian North and am excited to explore these interests alongside the class in this new context and learn from Yellowknife leaders.

Hi, I am David Roberts, an associate professor in and the director of the Urban Studies Program at the University of Toronto. I joined the Urban Studies Program in 2013 after completing my PhD and MA in geography from the University of Toronto. Prior to that, I worked for several years at a shelter for homeless and refugee teenagers in Seattle. It was my experience working in the shelter that really piqued my interest in urban issues and urban life. This work also cemented my commitment to imagining and helping realize more liveable and just urban futures. I try to embrace this commitment throughout all my activities as a professor and citizen of the University and City of Toronto, most notably through my research, community engagement, and teaching practices. I am excited to learn and work with this class as it is an opportunity to learn from those that led the response to the 2023 wildfires and to meaningfully contribute to improving emergency responses in the future.

Hello, I am Esther Tang, a forestry PhD student from Thomas Lab. My research focuses on biochar applications in a forest restoration context, specifically in post-fire and mining sites. I am trying to understand how tree seeds and seedings respond to pyrogenic carbon and biochar.

For this Yellowknife project, I am interested in learning about their forest management strategies related to fuel management and firebreaks. My focus will be on addressing forestry waste generated in Yellowknife due to wildfire prevention and exploring potential mitigation strategies.

Hello! My name is Lilian Dart (but you can call me Lily!) and I am a PhD student in Geography at the University of Toronto. My doctoral research examines grassroots environmental activism and social movements in the context of Canada, and I am particularly interested in conflicts around the conversion of green space for housing development. I have a significant professional and academic background studying housing and homelessness related issues, where I have researched and written about the jurisdictional responsibility for housing in Canada, creative approaches to addressing the housing crisis in mid-sized cities, and community-based service organizing. I am a believer in the power of community in addressing, planning, and responding to the problems that face our planet. I plan to research the collaboration and communication among the homelessness-serving sector during and after the wildfires, aiming to understand what went well and what could be done differently. I look forward to learning from and working alongside the residents and leaders of Yellowknife!

Hi, I am Léo Jourdan, an MScF (Master of Science in Forestry) student at the University of Toronto. My research focuses on detecting burnable fuel in forests through the analysis of lidar scans. Ultimately, the outcome of our work is to better predict fire behaviour, including near communities and infrastructure. I spend my (limited!) free time in a local climate justice organization, where we connect climate and housing issues, and aim to materially improve the conditions of tenants in the city through concrete, on-the-ground organizing. As such, I am particularly interested in the ways in which communities are empowered to protect their physical spaces through fuel management. When in Yellowknife, I’ll be thinking about the best ways to include all community members in initiatives that keep their homes safe from fires. I am excited and grateful for this opportunity, and I am really looking forward to our time in Yellowknife.

Hello, I am Sara Tamjidi, a Master of Public Health in Indigenous Health at the University of Toronto. I am a settler and first-generation immigrant from Iran. Drawing from my experiences and upbringing, I am deeply committed to building solidarity ties between historically disenfranchised communities as a means of achieving collective liberation, which informed my pursuit of my master’s focusing on Indigenous health.

My research interests encompass climate justice, the intersection of the climate crisis and health, and leveraging knowledge mobilization as a tool for empowerment. Currently, I am working as a Research Assistant at the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Research Laboratory (PRRL), where I am examining the impact of wildfires on remote Indigenous communities in northern BC and exploring innovative solutions to address these challenges. While in Yellowknife, I am eager to learn from those who led the response to the 2023 wildfires and to make a meaningful contribution to enhancing future emergency responses, all over the landscape. By learning from one another, we can apply our shared knowledge in diverse settings.

Hi everyone! My name is Ava, and I am a student in the Master of Community Health program at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health. I am in the addiction and mental health stream of the program, so we examine this topic at the population/community level and through the lens of various intersections, alongside things like the social determinants of health. Throughout the pandemic, I have been working on mental health crisis lines and have observed the profound impact of climate change and housing issues on people’s mental well-being. This has fueled my interest in the impact of climate change on health, planetary health, and the specific impact on mental health. I am eagerly anticipating the trip to Yellowknife to apply knowledge from my courses and research interests, and to expand my understanding through interactions with the city’s leaders and residents. I am also very excited to be in an interdisciplinary course with students and professors from various programs and be able to learn from their expertise!

Hi, my name is Ashwini Gadtoula, and I am going into my second year of the Master of Science in Planning program at the University of Toronto. My interest in planning has been informed by my fascination with how each place can be uniquely reflective of its residents and evolving to mirror their vibrant communities. In this way, the discipline feels rather alive, much like our cities. However, there are tensions, as the potential for growth does not always translate into changes that benefit everyone equally. As a planner, I am interested in the stories of folks at the margins, because I find their perspectives often complete the picture of the city and reveal significant aspects of its true character.

I am particularly keen to learn the stories of Yellowknife residents, piecing together the kind of tailored policy approaches needed to mitigate the circumstances they have been faced with. Throughout this course, I plan to reflect on questions about what it takes to balance and respect self-determination while also seeking to develop inclusive strategies for communication, housing, and climate resiliency. I am looking forward to exploring how planners can be more effective in the Yellowknife context, by embracing the unique visions of residents and moving away from historic planning practices that are rather imposing and predetermined.

Hello everyone! My name is Roya, and I am heading into my second year of the Master of Science in Planning program at the University of Toronto. Leaning towards the social side of the field, I am learning how to plan for safe, sustainable and equitable spaces through policy. Currently, I am interested in planning for the youth, in terms of the built environment and policy. Growing up in the suburbs of the GTA, I constantly reflect on the challenges these built forms pose to youth. I want to bridge this interest with policy work, finding ways to plan, promote and maintain vibrant communities fit for everyone. I am excited to participate in a multidisciplinary course which gives me the opportunity to learn from my classmates who come from a diverse range of fields.

Studying in a major city like Toronto, there is a significant gap in learning about planning and challenges in northern communities. So, I come to Yellowknife ready to learn and listen about the response to the wildfires, seeing how issues such as housing affordability, environmental sustainability and colonialism intersect in the built environment. I am curious about the role of planning and policy in adapting to the pressures directly caused and exacerbated by climate change. Ultimately, I hope to support the community by making meaningful contributions to future response efforts, before, during, and after such emergencies.

Hello, I am Amélie Zarir, and I am a student in the Master of Anthropology at Laval University in Quebec. I will be pursuing a PhD in Anthropology at the University of Toronto next September. In my MA project, I focus on food alternatives within an agricultural sector damaged by nuclear tests (1966-1996), the COVID-19 pandemic and climate changes in French Polynesia. During a three-month fieldwork, I examined the daily experience of farmers faced with these crises, further exacerbated by unequal land ownership opportunities and a globalized market favouring low-cost imported food over small-scale local production. This led me to understand how these compounded crises have led to self-sustainance as an effective enviro-political strategy to counter Polynesian food dependence, and economic dependence from mainland France. Sustainable agriculture in the region is likewise threatened by biomass burning activity from South and Southeast Asia, which produces plumes of smoke travelling over the South Pacific. These issues have prompted me to design a doctoral project aimed at understanding the overall environmental dynamics in the Indo-Pacific Rim, especially regarding the governance of forest fires in Indonesia. I will also focus my lens on the Northwest Territories in Canada to give me a better understanding of forest fire challenges.

In Yellowknife, I intend to research how wildfire management is deployed, especially throughout the emergency plan, and how it is experienced locally. I look forward to understanding how indigenous knowledge is integrated into institutional decisions about wildfire management, thus questioning temporality and land management. I am eager to share this experience with all of you!

Hello everyone! My name is Claire and I am going into my second year for a Master in Global Affairs candidate at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. Much of my research has focused on Canada’s North and Arctic Region. For example, my undergraduate degree in criminology and my current master’s research on digital security has allowed me to unpack the evolving borders and geopolitical dynamics in the Arctic and its impact on Indigenous communities. I do this research through an intersectional lens, looking at the ways gender, colonialism, and international development interact to create unique challenges for individuals.

I am so eager to expand my Arctic and Northern research in Yellowknife! Tree planting in Northern BC and Alberta last summer piqued my interest in this course as planting in burned land opened my eyes to the immense disruption wildfires create for communities and the environment. While having these lived-experiences of planting trees in burned forests and doing research in Arctic regions provides me with relevant perspectives to examine the 2023 wildfire season in the Northwest Territories, I come to this course with an open mind. Learning from my fellow classmates and individuals across Yellowknife deeply excites me.

Hey everyone! My name is Ryan and I’m a student in the Masters of Landscape Architecture program at the University of Toronto. This past winter, I was part of a class titled “Land(scape) and Memory” which was an intersection between the fields of Landscape Architecture, Memory Studies, and Indigenous Studies. The class examined cultural conceptions of land and landscape in relation to identity, ethics, cultural narratives, and political history. My research focused on the effects of climate change in the Global North and ways to design on land that is subject to disaster; specifically, how to design cemeteries in the North alongside a thawing permafrost that causes flooding and erosion.

In Yellowknife, I hope to explore the relationship and intersection between Indigenous resilience and landscape designed with resilience in mind. I also look forward to the opportunity to work alongside colleagues from a variety of disciplines that all overlap with Landscape Architecture studies