If you can’t afford a car or Uber, and there’s no major public transit route in your neighbourhood, finding a job and keeping it can be an uphill battle.

It’s an all-too-familiar challenge for up to one million urban Canadians, according to an estimate by U of T geographers Jeff Allen and Steven Farber, who published their findings in Transport Policy last month.

The authors used household demographic and employment data from the 2016 census, among other information, to do a national accounting of so-called “transport poverty” across the country for the first time.

“We know how many poor children there are in this country, we know how many recent immigrants there are, but no one has ever known how many people are transport-poor,” says Farber, who is an assistant professor in the department of human geography at U of T Scarborough.

He and Allen say they hope their research will help inform government policy on transportation.

“In Canada, governments are currently investing billions of dollars in public transport with very little guidance on whether and how this infrastructure can be used to achieve a higher degree of transport justice in Canadian cities,” they write.

What does it mean to be transport-poor? Farber says it’s a mix of disadvantages: socioeconomic status (low income, ill health, being a recent immigrant or elderly) and a lack of access to transportation (being unable to afford a car, or reach destinations easily by transit, for example).

These circumstances can create a vicious cycle, he adds. “It can have long-run implications on your quality of life and well being,” he explains. “Your ability to access goods and services, your ability to access the political process, your ability to find work and keep a job – that all feeds back into your socioeconomic status.”

Allen, who grew up in Toronto, says it’s a topic that’s long been on his mind as he noticed the range in transit services available across the region. Now a PhD student in physical geography, he and his supervisor Farber looked at the problem in Canada’s most populous urban areas: Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa, Edmonton, Quebec City and Winnipeg.

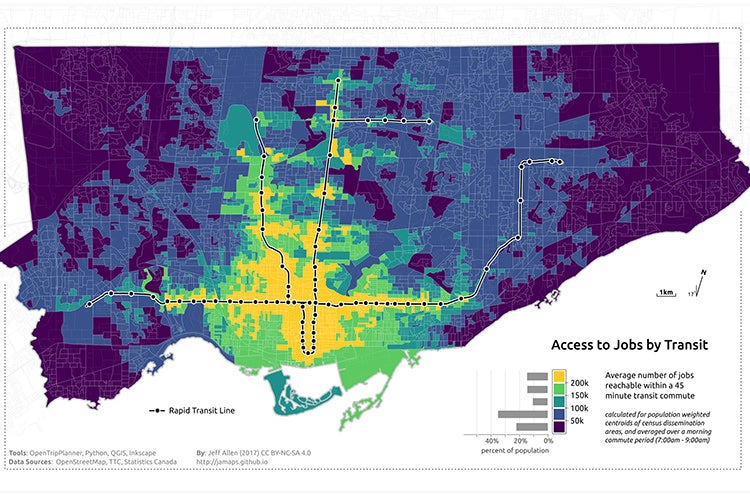

A screenshot of an online map created by Allen and Farber that shows access to jobs by transit in Toronto (photo courtesy of Jeff Allen)

“We find that within Canada’s eight largest cities, 5 per cent of the total population are living in low income households which are also situated in areas with low transit accessibility,” they write. “This totals nearly one million people who are at risk of transport poverty nation-wide.”

In an online map, they plotted some of their data to show access to employment opportunities across these cities. Zooming in on Toronto, one sees that people who live downtown have a wealth of opportunities, but they become more scarce farther out from the city centre.

When it comes to transport poverty specifically, the researchers pointed to two types of at-risk neighbourhoods. The first are the inner suburbs: low-income, high-density communities living in apartment towers. Neighbourhoods like Flemingdon Park and Thorncliffe Park in Toronto are relatively close to downtown, but they aren’t situated on high-order transit routes. They’re also home to many low income and recent immigrant households who can’t afford a car. The other typically transport-poor neighbourhoods were outlying low-income suburbs like Scarborough, pockets of Markham, Etobicoke, Oshawa and Brampton.

As more and more people find themselves priced out of downtown – a trend known as the suburbanization of poverty – more households could find themselves living at a transport disadvantage, Farber said.

Their paper references and builds on the work of the Neighbourhood Change Research Partnershipled by U of T Professor David Hulchanski, that has documented the growing gap between rich and poor in Canadian cities.

Farber says there hasn’t been much weight given to transport poverty in decisions about where to put new transport infrastructure or add transit routes. “They’ll give a project bonus points if it goes through a low-income neighbourhood,” he says, “but they haven’t really been up to speed with what’s been going on in academia and other jurisdictions where there’s been more of a concerted effort.”

By putting the problem on the map, the researchers hope to change the conversation and raise the issue to the national level.

“The bigger the problem, the more important it is that we solve it,” Farber says.