Project team:

- Giidaakunadaad/Nancy Rowe, Michizaagiig, Ojibwe of the Anishinaabek Nation, located at New Credit First Nation

- Dr. Bonnie McElhinny, Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto

This City Research Insight features the work of Giidaakunadaad/Nancy Rowe and Dr. Bonnie McElhinny on the project “Water Gathering with the Credit River: Decolonizing municipal and provincial understandings of land, parks, and rivers” from the School of Cities 2020 Anti-Black Racism & Black Lives and Anti-Indigenous Racism & Indigenous Lives Funding Initiative.

This project was one of 13 supported by the School of Cities through an Anti-Black Racism & Black Lives and Anti-Indigenous Racism & Indigenous Lives Funding Initiative. This initiative supported anti-racism education, outreach and engaged praxis, and policy-oriented research projects and initiatives undertaken by faculty and student associations at the University of Toronto, and with the wider community.

The School of Cities is excited to share this special issue of City Research Insights to present a November 2022 oration by Giidaakunadaad/Nancy Rowe, Michizaagiig, Ojibwe, Anishinaabe Kwe of the Mississaugas of Credit First Nation. This oration focuses on history, colonialism, and the Water Gathering. Giidaakunadaad/Nancy Rowe and Bonnie McElhinny edited this Insight as a process of transforming the genre of the policy brief in appropriate ways and translating knowledge in this form.

In 2020-21, the people of Akinomaagaye Gaamik (Lodge of Learning), led by Giidaakunadaad/Nancy Rowe of the Mississaugas of the Credit and in collaboration with University of Toronto faculty member Bonnie McElhinny, organized a Nibi Aawin Maadziwin (Water is Life) Gathering with Ziibii (the Credit River). The first three-day Water Gathering occurred in July 2019 at the Credit River, Erindale Park in the City of Mississauga. It was, to our knowledge, possibly the largest and most public gathering following appropriate protocol and propriety at and with Ziibii since displacement of the Michizaagiig (now known as Mississaugas of the Credit) in 1847. Giidaakunadaad and Bonnie talk about the Water Gathering in this video by Cher Obediah.

Organizing the gathering required complex and critical conversations with the City of Mississauga and the Credit Valley Conservation Authority, which co-manage Erindale Park, as well as with the University of Toronto Mississauga, which is immediately adjacent, about municipal and provincial park bylaws and guidelines that restricted access to the waters and the land. While these initial conversations in 2018-2019 helped to set precedents that supported aspects of the gathering in 2019, Akinomaagaye Gaamik found that they had to explain and reiterate previously reconciled issues for subsequent gatherings in 2021, 2022, and 2023. These gatherings, together, diagnosed significant barriers and challenges that need to be addressed. The City and the Conservation Authority need to establish the full set of bylaw, guideline, and policy changes needed to uphold Indigenous, inherent and human rights and educate municipal and conservation employees so that they do not continue to create barriers to the land.

Parks and colonialism

Parks are often understood as a commons for the public. However, the creation of parks has displaced and continues to displace Indigenous people:

“In these early days of parks creation in Canada, Indigenous Peoples were understood as obstacles to the enjoyment of nature. Thus, they were often forced to relocate or were restricted by imposed jurisdictions that effectively eliminated… Indigenous practices and economies …”.¹

Existing bylaws continue to make many practices in Indigenous gatherings illegal. In planning the Water is Life Gathering, many understandings of water, of governance, of history, and municipal and provincial policy guidelines need to be reconsidered. Conservation Authorities manage more land than any other entity in southern Ontario; developing anti-colonial and de-colonial land-based policies are key to reconciliation and the preservation of inherent rights of Indigenous peoples in these sites.

We are lake and river people

We are lake and river people. Our territory is our everything, our Anishnaabek Waakiing. It’s where we derive our sustenance. It’s where we operate all of our institutions: social, legal, spiritual, educational, etc. It’s where we do knowledge transference to our children and our grandchildren. It’s our everything. Our life source from which we derive everything for life. We’ve been here a long time. We know what they now call Ontario. We know her well. We’ve been here all along. We know our rivers. We are now called New Credit or “Good” Credit Indians – I forget what they’re calling us today. But our real name is Michizaagiig. Michizaagiig not only describes who we are as a people, but literally places us in the location that you are sitting in, if you could understand.

We were physically displaced and dispossessed of our territories. That wasn’t by accident. It had nothing to do with us not comprehending or not being literate. It had a lot to do with colonialism, racism, and discrimination. That’s why I’m sitting way over here, an hour and a half away from you. I’m sitting way over here on five little concessions of land with no river, and that’s very important. We are Anishinaabek Michizaagiig people.

Remember I’m talking to you from a reservation.

We live under different laws, we’re still controlled by the Indian Act. We’re still being governed by implanted colonial governance systems. So we’re not living the life that our grandmothers wanted us to have when they said yes to the newcomers. The grandmothers, by way of treaty, agreed and said:

“Yes, let them come so they can have a good life too. They can stay, but they can only stay under these conditions. They can’t take the land, water, earth, air, fire. All of that has to be taken care of, because both our grandchildren are going to need to depend on those things for their life, whatever it is that adds to their life, whether that’s education or food, whatever it is.”

Michi Saagiig history

According to Gidigaa Migizi (Doug Williams),

Our stories go back to the ice ages when Nishnaabeg moved into this area and the ice was still here. The Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg lived here and they were traditionally the people that fished the Atlantic salmon that came up the St. Lawrence River and spawned in the great rivers that flowed into Lake Ontario.²

It’s not just the river

Maps need explanation. This map shows our territory and our reserve. The yellow part is our territory. Some people don’t know whose territory they’re in – that’s Michizaagiig territory. The amplified part is the reservation. It’s only five concessions. It has impact, this map. That’s what we’ve been displaced and dispossessed of. Then you look and see all the waterways there, remember I was saying we’re lake and river people. So, it’s not just the Credit – it’s all those rivers. The Etobicoke, the Humber, all the way up to the Rouge and then down to Long Point. Maybe in peoples’ minds we’re the Credit River, New Credit people. Maybe they just think we were placed along the river, a few Indians along the river. But I want them to know that it’s not just the river.

Many people are concerned about food security right now. It’s interesting that in our territories nobody ever thinks about our food security. We have no river. We’re lake and river people, but there’s no rice to harvest here. There’s no salmon, there’s no trout. It’s all clay farmland. One of the things that I’m tasked with is to know our pharmacology, what people call medicines, but I can’t do that here. It’s the river and the land that has our original pharmacy – remember I said it’s our everything, that includes our nutrition and healthcare.

But people are not concerned about our healthcare, nutrition, and education systems of the land and rivers, because they don’t know we need the river, or that the reservation does not have a river. People are not concerned about the salmon or whether we have access to harvest and eat the food that our body has known for thousands and thousands of years, like the rice, medicine, trout, and salmon. I would like to have my grandchildren know and learn about this, from proper Anishinaabek river and fish experts, with methods, delivery, and intelligence that is not west-determined or dictated.

The Anishinaabek truth about that river, and I’m talking about all the rivers, all the water, not just Ziibii, is that our existence depends upon that river and not in a mystical spiritual way, but in a very healthy and life sustaining way. We need that river, not just for thirst. We need it for our health care. We need it for food security. We need it for education. We also need her to help us understand science, Indigenous science. Not Indigenous ways of knowing – Indigenous science.

Why can we talk about Western science all day but when it comes to Indigenous people we use “ways of knowing” or “Indigenous knowledge”? You know the power of words. We need to help people understand, to put those things on par. Indigenous science, what they call “stewardship” today, has kept the people, land and water healthy for thousands of years.

We only walk here, and we only borrow from our grandchildren. It is their rightful inheritance to receive it all in pristine if not better condition. You and I are the grandchildren of pre-colonial agreements and treaties. You and I, all of us, are protected by those laws. We are supposed to receive water, earth, air, and fire: the life sources, in pristine order, because they are the minimum requirement for life existence. Clean air, clean water, clean earth, clean fire as outlined in Aanishinaabek Inaakninogayewin and the treaties.

Exercising those laws of this land is not us trying to get in the way of progress. It’s us trying to preserve and protect what little is left for our grandchildren. Did anybody ever mention reconciliation with that river? And I don’t mean that as some mystical spiritual concept. I mean that as a real scientific environmental concept. Remember I said pristine or better. But who’s cleaning her, helping her, if there are no voices talking about what I’m talking about here? And this is what I want to talk about with people. If there are no voices, then it doesn’t happen. It doesn’t happen if I’m not at that table when you’re talking about food security, if I’m not at that table when you’re talking about the river, or we haven’t spent time together where I could share this with you so that in my absence I know that you’re going to be thinking of my rights and about our grandchildren and their life sustaining inheritance when we’re making those decisions in those institutions.

When I come to the river and I say, “I have inherent rights and they’re inalienable, they’re inextinguishable because I am Anishinaabek. I have rights in accordance with our legal, social and political structures, and I know those things”, as soon as I say “inherent” – nobody knows what that means – they can’t even imagine it existing. They can’t imagine rights existing in the pre-colonial period. We’ve been here for 15,000 years. And I say,

I’m not rights-seeking: I’m rights-bearing. My rights pre-exist what is now called Canada.

Aanishinaabek Inaakninogayewin (Aanishinaabek Law)

Debenjiged gii’saan anishinaaben akiing giibi dgwon gaadeni mnidoo waadiziwin. Shkode, nibi, aki, noodin, giibi dgosdoonan wii naagdowendmang maanpii shkagmigaang. Debenjiged gii miinaan gechtwaa wendaagog Anishinaaben waa naagdoonjin ninda niizhwaaswi kino maadwinan.

Zaagidwin, Debwewin, Mnaadendmowin, Nbwaakaawin, Dbaadendiziwin, Gwekwaadziwin miinwa Aakedhewin. Debenjiged kiimiingona dedbinwe wi naagdowendiwin. Ka mnaadendanaa gaabi zhiwebag miinwaa nango megwaa ezhwebag, miinwa geyaabi waa ni zhiwebag.³

Treaties

Treaties are Anishinaabek Law – agreements; not meant to sell nor extinguish rights to lands or resources, but to determine how land and resources can be shared for the equal and mutual benefit of all beings, including water, earth, air, in the present and for future generations.

Understanding history is so important now

Understanding the history of the land, water, and people is critical. But something happens when someone like me comes in and sits with the people from the local, provincial, and federal institutions, whether it’s the University of Toronto or the Ministry of Education or Justice. I go there and I’m talking and educating but they can neither hear nor understand. And that is one of the biggest things that I recognize, not being listened to or understood.

I’ve been trying to translate for people to help them to understand and lay out for them: this is what Inherent Rights are. The thing is, people can’t even imagine that they (Inherent Rights), us (Michizaagiig), or her (Ziibii) exist. That’s what I call the colonial bias. The way the citizenry was educated, they don’t even know a couple of critical questions about us. I ask: who are the Anishinaabek? Where do they come from? Where do they live? Where are they located? What kind of food do they eat? The citizenry was trained to have these ideas about us. We don’t exist anymore, our river is not ours anymore, we and her have been removed, re-named, re-placed, out of sight, out of mind, forced to a reserve numbered 40A, called everything and anything except what we call our river(s), lands, and ourselves. Those beliefs still play out today. The citizenry who makes up the institutions, who makes up the media. This is what they’re operating from when it comes to us. They heard something or read something, and all of that has developed a series of myths I call colonial “myth-understandings”. Those myths are their truths rooted in ahistorical assumptions and stereotypical depictions of us: romanticism, fetishism, tokenism, eroticism, exoticism. You name it. So many -isms to support, maintain, and perpetuate colonialism are excused as colonial confusion about anti-Indigenous racism, discrimination, and harm rooted in a lack of knowledge.

I live, know, and understand how much harm and violence is being perpetuated due to the lack of awareness and understanding of us, our water, and our land. If I want to go to the river, I’m going to be courteous and I’m going to educate along the way as opposed to just going and exercising my rights. And that’s partly to protect myself and prevent harm, because I know I’m going to be harassed and discriminated against knowingly and unknowingly.

Now after seven years of work on these gatherings, it still occurs, and has even escalated, in over-policing, elaborate bureaucratic barriers, bureaucratic missteps, misogyny, paternalism, dismissiveness. There are new colonial hires in the role of “Indigenous Relations” that claim to represent, but actually contain and segregate. That was a big teaching that we got from the Water Gathering, but we understand it to be rooted in a lack of education, because people are not able to hear what we are saying. But after seven years now with the City authorities not hearing, not listening, and forcing us back to the beginning every year, this work is exhausting and at times feels hopeless due to a lack of accountability. It feels like humouring me and biding time until I go away. It’s not a good feeling and not a healthy relationship.

Western institutions can’t actually “decolonize”. Only the original people can decolonize. How exactly then, does a colonial institution decolonize? It’s operating from Western ways and everything, so it can’t actually decolonize. But there is work for institutions to do: by examining, developing and engaging in anti-colonial or uncolonial practices, which means being less colonial in procedures, processes, relationships. Education from historical, geographical, political and legal truth, according to us.⁴

I think it’s important to understand the enormity of the knowledge gaps and how they contribute to harm. But we have to start somewhere. We have to do something. The Water Gathering is a good place to start for these relationships and knowledge building.

Water Gathering with Ziibii

The Water Gathering is knowledge transference, knowledge mobilization. And with permissions, we are transferring that knowledge. We open it publicly despite the potential for harm and violence. The head people (experts) are aware. And so, people are welcome to wander and come and sit in, because to me you have to be there: experiential learning, I think they call it. You’re going to understand more by sitting there and listening because I don’t carry all that knowledge. I’m going to set you in front of the people who do, and they’re going to educate. The piece for us is actually the revitalization.

Remember I told you, we got no river at New Credit Reservation 40A? Can you imagine, I was 48 years old. Our first-year water gathering, that’s the first time I set my feet in her. Could you imagine? Was that knowledge? Did I learn something? What did I learn? Does that belong in the Western institution? Does that belong? Is that secret, do we keep that over here? My grandchild set his feet in there too. He got to know his river. I’m an old lady and I’m just starting to get to know my river. How do we translate what the Head Grandmother and Grandfather taught, so that the West could understand? They don’t understand because we’re coming from two different worlds.

It’s not an event, it’s not a festival. But it is open for people to come and observe and be respectful. Everything doesn’t go out because we know, some things could go away and be extracted and reproduced, turned into a resource, romanticized, and eroticised. I believe though that people, if they see us in our institutions, that will help them to humanize us. That’s a very important thing when we are engaging in decolonizing or uncolonizing work, is the humanization of Indigenous Peoples. To understand, witness. We are real people, sometimes called the Inherent Rights holders, who want to depend on this river. Myself and my family are Inherent Rights holders who want to fish salmon there and preserve them and eat them. And I want to teach my grandchildren their birthrights as Aanishinaabek. But I want to do that without interference. That’s a Nish law, non-interference. I don’t want to do that to the detriment of other people. But for some reason, when I see people at the river, they always think I’m infringing somehow on their space and their rights. I think we’ve got a clash here, and we’ve got to figure out how to stop that.

So, the Water Gathering, there’s so much knowledge that comes from the orators, educators, and experts that we select. The speakers at the 2019 and 2021 gatherings included Abraham Bearskin (Lead Grandfather, educator) and Cheryl Littletent (deceased, Lead Grandmother, educator), Dorothy Taylor, Lyndon George, Dr. Deb Danard, Autumn Peltier, and others. So that transference of knowledge can come here and be revitalized here; so much of that was taken by education and colonialism. The knowledge revitalization here – that’s reconciliation. Those grants provide the means to have that process play out. It got me to my river. It got people who carry that knowledge there. I carry just a little grain of sand. I still have a lot to learn. And sharing – that’s a law. And we share that with people who come. We had hundreds and hundreds that first year. And hopefully they understand and become aware of the importance of the river beyond recreation and fishing, but for life. They come and they educate, but they educate from our pedagogy and they use our curriculum content.

I don’t like to use the word ceremony, because it invokes these mystical, spiritual ideas about us. But we have our way. We do research. And it’s not necessarily the same as the Western way. We say knowledge comes from everywhere and everything. Not just humans. Most research methods are not in alignment with Indigenous research methods. But something that I thought was workable was participatory action research. You’re not just helicoptering in and extracting, going and getting a paper published or a PhD or whatever it is, reaping the benefits of what you’ve done. You’re actually doing something that is in alignment with the Indigenous paradigm, which is reciprocity. So, we found something and we’re going to come back regardless of whether the funding gets cut or not, and we are still going to carry on and help create the change that is necessary. Me going to the water is me exercising my right. The big picture was for us to have unfettered access to our everything and exercise self determination. But if I go there, there are going to be barriers and a whole other set of criteria kicks in when it’s Indian people.

“Get to know your river” is Indigenous research

This research on this river involves Indigenous Peoples, their ancient knowledge, practices, customs, and lifeways. Thus, the paradigm, agenda, purpose, process, and outcomes are built around these premises. While offering a clear-eyed overview of histories of settler colonialism, it also elaborates an alternative. It is founded on Indigenous processes and practices that are not the same as western linear perspectives. In considering the intertwined health of land and people, this research reflects an Indigenous perspective on time and the events in Creation that help to restore balance and purpose, and specifically educate and empower Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Peoples.

I went to the river to exercise my rights. Giving them notice and all of that – it was a learning. It’s not about the Water Gathering. It’s about access. The bigger picture is access and normalizing me going to my river and not being harassed along the way. We did everything in the front to prepare for that. We knew the City bylaws about fires and the things – fees, how I’m going to be taxed to go and sit by my river. Wait a minute – what does Aanishinaabe Inaakninogayewin say? We did this in a very good way, in a very humble way. But when I went, the first time they didn’t hear me. But Bonnie, they could hear her because she speaks their language, and they allowed us, which is really interesting. Remember I’m a rights bearer – but they allowed us to come in. And we got the permissions, even though I know I don’t have to. I know my Inherent Rights are protected. I know I can exercise them, but I don’t want to do that – to cause disharmony – and so we chose the path of educating everyone in the brief moments we were afforded. We open it up to the public, and the Elders there are the heads of that, and they tell us everything that needs to happen, and we are the helpers – Bonnie, I and so many others – we’re the helpers. And everybody is using what they have, their skills, gifts, expertise, resources to ensure this thing happens.

This is not a festival, it’s not an event. It’s getting to the river, learning and putting our law and responsibilities to her in praxis. And I want to do that unfettered. But I think ahead of time, what’s going to happen if I go down there without a license: I’m going to get harassed, I’m going to get questioned. What’s going to happen if I want to practice my responsibilities in accordance with our spiritual, legal, cultural institutions, what’s going to happen? I’m going to be interfered with. What I offer to them out of kindness is I say, “You know what, I think there’s a gap in understanding across your system about Inherent Rights. Can you afford me some time, and I’ll sit and visit with you, and I’ll help you understand what I’m doing here?” That’s alerting us to an area that we need to be examining. We’ve learned that there’s severe knowledge gaps within the park police enforcement and authorities with both the City and the park. So how can we address that?

Gwayeakwaadziwin: Getting beyond reconciliation

It feels like we’re shooting in the dark. We don’t have the tools, the information that we need to make decisions. We are not going to dance, craft, or wish and pretend our way out of colonialism. What we need to do is sit down and figure out how to operationalize reconciliation, the real work. How do we do that? In the past we tried using colonial systems, structures, protocols, and processes to address colonial harms. But if it didn’t work before, it’s not going to work now.

We have this term, gwayeakwaadziwin, and what it means is when we’re going to make major decisions, and we’re going to operationalize something, we want to make sure it’s set up right at the beginning. That we have all the right people at the table with all the right gifts and all the right skills and all the right resources. And we don’t make a move, we don’t make decisions unless we have everything in order, because then we can be guaranteed of its effectiveness and efficiency. It doesn’t mean it’s going to be perfect, it means we have properly prepared.

A couple of years ago I said, “I’m so tired of them coming for a paper, or to ask me to look at a curriculum, develop a lesson plan, advise on a city or government project, etc.” At the end of the day, it was grains of sand on a beach just checking boxes of ‘incorporated Indigenous knowledge’ and ‘consultation’, and not leading to or developing sustained and lasting change. Still they say, “I want to know about Indigenous ways.” Okay, but you only come for a day, and we never get to have a conversation about how to uphold and protect Inherent Rights, never mind collaborate, codevelop and construct, and implement substantive resolutions. The colonial timelines have us running out of time.

I want to help address these issues because I want to be put out of work so I can spend time with my grandson on the river.

But when you think about the Western way, they just want the product. “Oh, I can’t get this person, so I’ll just get this other person”. There’s a stereotype thing in there – I call it “any ole Indian will do.” We’re going to talk about Indigenous rights, and we’re not going to bring an expert in law and policy? We’re just going to call any ole Indian, they may not have any experience or anything to do with that kind of thinking. And that is so interesting, because if you were doing something that involved Western academics, you’d absolutely 100% be sure that that person was disciplined in that area to help you make those decisions.

We have this official policy of “reconciliation.” But it’s not being operationalized – it’s aspirational. I say, “hashtag reconciliation” and I say that a bit sarcastically. I believe someday we will privilege the right and proper voice, vision, and jurisdiction(s), once we take time to sit and listen. I’ve been working hard the last couple of years to understand how to translate that for the native and non-native people. How do I translate that for your average employee or staff in the institution? Bring them to an understanding of what is Inherent Rights, what is Indigenous rights, and how do we uphold them?

People are making land acknowledgements to move towards reconciliation. They are a powerful, easy and useful tool, but they’re still putting opinions, perspectives, ideas in there that are not truth. They are not fact and evidence-based, and then I come along. I said, “Well, show me the research.” Well, it’s really hard because it’s only Western research. I could sit here for days and tell you what’s wrong with Western research myth-understandings that are still held as truth about us now. Land acknowledgements are powerful, but do they include any types of actions? Can you operationalize them? They’ve gone performative, and I’ll be honest, the land and I are tired of being honoured, acknowledged, and resilient. What we need is the operationalization of reconciliation plans laid out in multi-year plans for the University and all institutions. But how do we operationalize it? Is it for students, or staff, or faculty? What does the Inherent Rights holder need? I know what our law and treaty is, so what is your role, or the institution’s, and all the citizens’ in attendance? What are their roles and responsibilities?

There are lots of people out there having a good life in our Anishinaabe Waakiing – our everything, our sustenance, our classroom, etc. – and they don’t even know we exist. The relationship is outlined in our law and furthered by treaty, but there’s people out there that can’t even name the Inherent Rights holders, applicable law, treaty, and/or agreements. We need to educate about that.

And my question is always – how is what people in our territory are doing having a direct benefit and impact on the grandchildren (Inherent Rights Holders) of those territories? It’s not about me. Are they able to go up to the river unfettered? Are they able to harvest the salmon? Where’s the rice?

That’s our mainstay. Can I educate my grandchildren about rice? No, I have to drive way up to Curve Lake because the rice beds down here are gone. Just some questions, probably provocative questions maybe – but I don’t think they’re that provocative. But just some assessment questions to ask themselves. Hashtag reconciliation. How is what we’re doing in the original people’s territory having a direct impact and benefit on those people? If we don’t know who they are, how can we even assess the impacts?

I expect things to change: procedures, processes, and policies. In my experience we are going to continue to give lip service to systemic, structural, institutional racism and colonialism, whatever you want to call it. When your policy says that the Inherent Rights holders are self-determining and Indigenous rights will be upheld – not acknowledged and honoured – Indigenous rights will be upheld in these institutions and no Indigenous person will experience racism or discrimination – then you have something that’s usable.

Work done and ways forward

The conventional format for this Critical Research Insights series asked us originally to list deliverables, work done, and ways forward… with a focus on other institutions. But there is also work to be done at this university. This has been a first step in initiating and building a relationship. Sometimes the first encounter diagnoses what needs to be done and raises awareness. The next step is continuing to build this relationship. What this looks like varies by institution. Don’t come to me and ask me for products, because I have learned that it’s the process that’s important. We need to engage in a process of awareness, learning, and understanding before we collaborate and develop anti-colonial resolve. How can a paper like this be used to translate without being asked to conform to Western knowledge practices? Support for generating this issue of Research Insights by beginning with oration is a step towards anti-colonial practice. While some of the insights developed through this grant have direct import for the recognition of Inherent Rights in Michizaagiig territory by the city and conservation authorities, others have import for what the University of Toronto can do to continue to support Indigenous research.

Lessons from the Water Gathering: How to challenge anti-Indigenous racism

During the Water Gathering planning in 2019, key municipal decision-makers and park and conservation authority managers in Mississauga asked Giidaakunadaad, “Why does the Credit matter? Does it have to be the Credit?” The gathering itself is a form of anti-racist and anticolonial education which shares knowledge broadly and diagnoses the work that needs to be done in order to ensure that gatherings can occur without interference or harassment.

Our experiences over the last seven years have uncovered severe basic knowledge gaps. After sharing knowledge with the City and conservation authorities, problematic practices continue to persist. An ahistorical policy process leads to the erasure of what was learned each year.

1.

Racist and misogynist actions rooted in a colonial power dynamic should have been avoided – especially after the learnings and precedents from the first year of the gathering. Failing to listen to Indigenous peoples’ experiences is minimizing. It erases and dismisses negative impacts and blames the victim.

2.

Existing municipal policies which led to overpolicing, charging fees for access, and imposition of colonial guidelines on Indigenous knowledge and practice and rights were repeatedly encountered in multiple years, and not proactively transformed to uphold Inherent Rights and challenge institutional violence and dismissal. This placed the burden of on-going anti-colonial education on Inherent Rights holders in ways that show a lack of commitment to anti-colonial practices

3.

When problems were diagnosed, and relevant City officials were offered formal education in regionally appropriate topics (the history of colonialism, anti-Indigenous racism, stereotypes, Inherent Rights), representatives of the City originally agreed, then balked. There has not been collaborative work with Inherent Rights holders.

4.

Some city representatives are now taking brief online training(s) on Indigenous issues. It is unclear whose interests are represented in these materials. Inherent Rights holders should decide what is appropriate training. Consulting other Indigenous people on behalf of key interlocutors is essentialization; amongst other things, this practice treats all Indigenous people as interchangeable and as a monolithic group, and eclipses Inherent Rights holders’ voices and vision. Repetitious re-educating of basics and fundamentals about who the Michizaagiig are and what their rights and connection to the river are on the fly is time wasted, labour intensive, and can result in poor decision making and anti-Indigenous racism.

Key recommendations for municipalities and conservation authorities

1.

Develop a policy for guaranteeing Inherent Rights holders’ unfettered access to the land and water, without racist interference and judgement by colonial processes now and in future. This will include outlining procedures to support self determination, Inherent Rights realization, and research to inform anti-colonial practice, which embody harm-reduction for ALL Inherent Rights holders.

2.

Policies, procedures, and decision-making must be in alignment with the Framework for Reconciliation – Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Calls to Action, UNDRIP, and the Ontario Human Rights Code – and in robust and on-going consultation, collaboration, and co-development with the Inherent Rights holders.

3.

All City and Conservation Authority departments and employees must be regularly and continually trained in Indigenous relations, in ways co-developed and vetted with Inherent Rights’ holders, to embody principles of harm-reduction and understand Inherent, Indigenous, and Human Rights.

4.

There must be clear and on-going accountability mechanism(s), such as annual reporting.

Key recommendations for the University of Toronto (including the School of Cities)

The challenges for the University are different. While policies exist, not all in the University are aware of them, or complying with them.

The University of Toronto generated a number of documents with calls for action in response to the calls from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and in support of self-determination. Some of these include:

While there exists a requirement for annual accountability from all faculties, departments and units many remain unaware of this requirement, and unclear about what a full response requires.⁵ The requirement is often treated as optional.

All University of Toronto academic administrators, faculty and staff must be regularly and continually trained in Indigenous relations, in ways co-developed and vetted with Inherent Rights’ holders, to embody principles of harm-reduction and understanding of Inherent, Indigenous and Human Rights.⁶

There is more work for those who are funding projects to do. The cycle of funding and what is supported are sometimes at odds with granting guidelines. There were four water gatherings called for, but only one was funded. Funding needs to be adequate, sustained, and reliable. This is a problem and a challenge for uncolonizing research, applying anti-colonial praxis, Indigenous research methodologies and framework, and respectful, reciprocal, and reconciliatory funding strategies.⁷

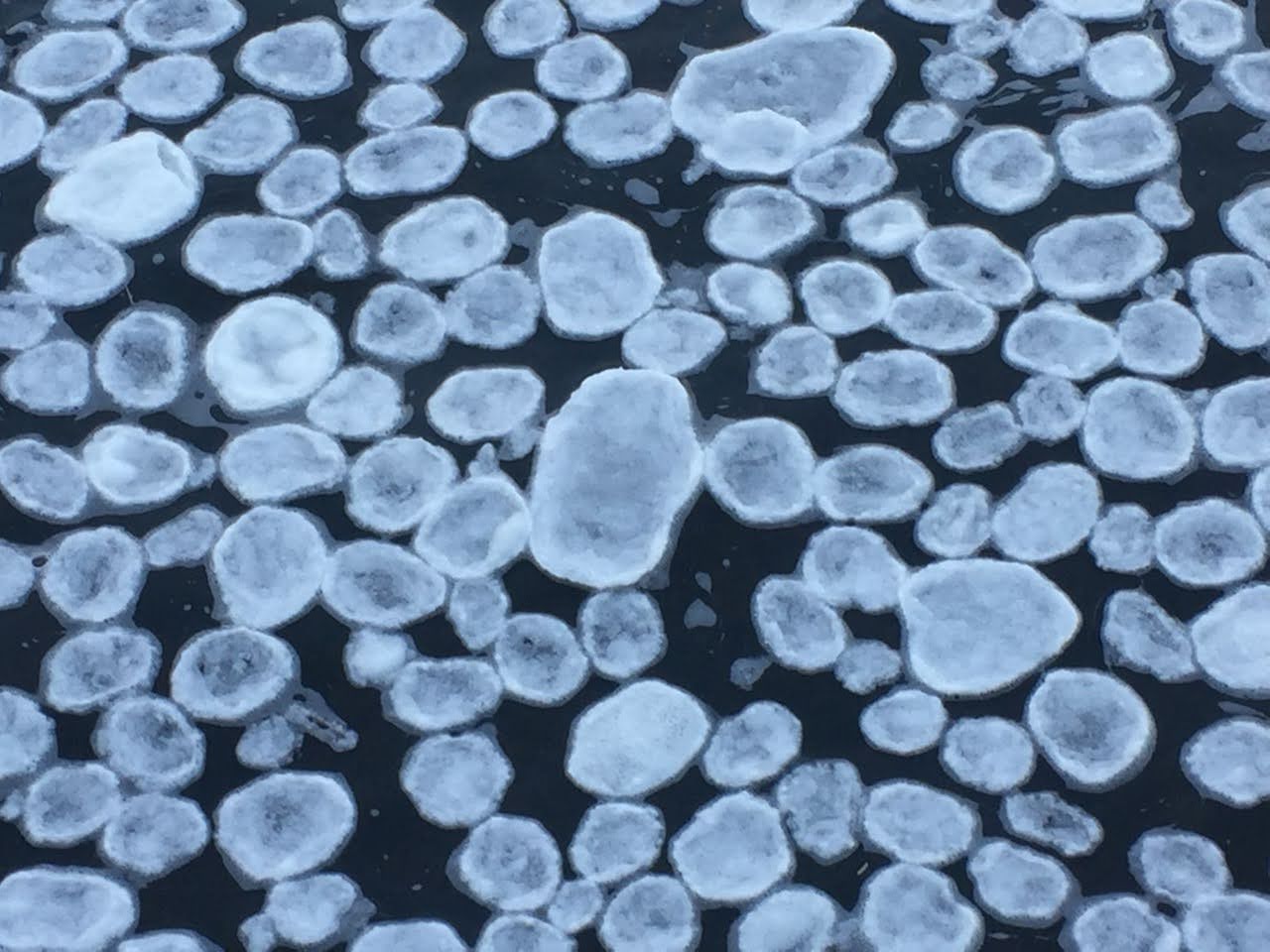

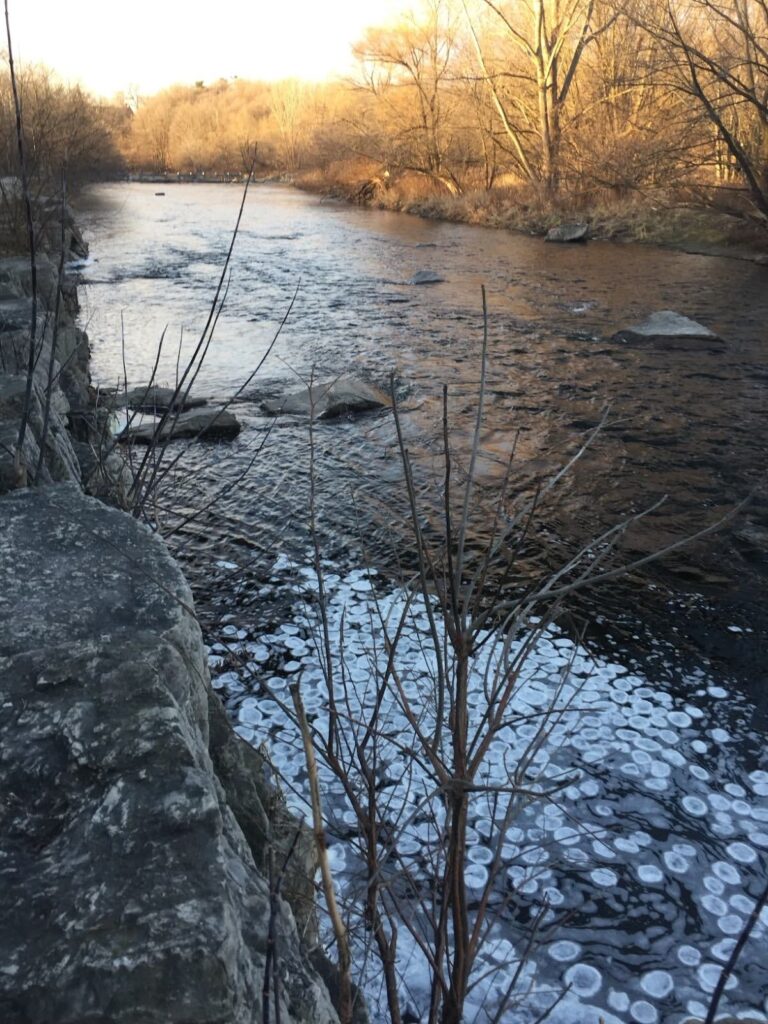

In Closing: A beginning. Shell ice. Water is life. Gathering with Ziibii.

This is where we started in 2018. It was the coldest day thus far this winter and we were gathering on and with Ziibii, at Erindale Park, in Mississauga, just down over the bluff from the University of Toronto Mississauga.

We are introducing ourselves to Ziibii, beginning preparations for a gathering that will happen in a few months. We spot some circles on the water. We imagine the worst — detergent? They are clustering together on the east side of the river, in a spot a bit protected from the current. Every few moments, another one floats down, and joins up with the cluster. Giidaakunadaad leads a ceremony, and the circle includes women and men from the lodge, NGOs, representatives from the City of Mississauga and Credit Valley Conservation Authority, students from University of Toronto and York University, and some other Indigenous leaders who have been trying to redefine land and sovereignty in urban settings. This is an exercise in ceremonial jurisdiction, and a redefinition of what conservation means. The Credit Valley Conservation Authority and City of Mississauga are learning they will need to override the bylaws that normally disallow camping and sacred fires, recognizing (though here they hesitate perhaps a second, and check in with each other) the sustainable harvest needed to create a sweat lodge. They are still learning.

We started the work in a good way. As the pictures from that day went up on Facebook, we all learned how the water speaks to us. Those circles, Becky Big Canoe and Waasekom told us, are shell ice. They are frozen eddies, and they are beautiful. It’s relatively rare, especially this early in the year, and in this place. Its formation requires water flowing at just the right speed and temperature. A good sign. Ziibii is introducing herself to us.

What’s next?

Giidaakunadaad continues working with institutions, including UTSC, to develop and apply policy and system-wide approaches to harm reduction via anti-colonial practice and education on rights (see document listed above).

During COVID, Giidaakunadaad recorded hours of oration with Bonnie, expanding on the key topics above. She is working with Bonnie on a book to share this research.

There have always been and will always be water gatherings. The gatherings will continue.

Regardless of barriers, obstacles, funding, and support, they must continue.

– Giidaakunadaad

Giidaakunadaad (The Spirit who lives in high places), Nancy Rowe is Michizaagiig, Ojibwe of the Anishinaabek Nation, located at New Credit First Nation. She is a recognized Knowledge Keeper and Representative of New Credit. She holds an honours BA in Indigenous Studies and Political Science. She founded Akinoomaagaye Gaamik lodge in 2014, to provide educational opportunities for all interested in Indigenous perspectives on life, health, education, history, and the environment. Akinomaagaye Gaamik has many partnerships that support on-going education in Ontario, Boards of Education, Ontario Principals Council, Ontario Human Rights Commission, Ontario Teachers Federation, Ministry of Education, University of Toronto and Indigenous Organizations.

Email: giidaakunadaad@gmail.com

Website: https://akinomaagaye.weebly.com/

Dr. Bonnie McElhinny is Professor of anthropology and women and gender studies at the University of Toronto. She directs Great Lakes Waterwork/Water Allies (waterallies.com), and is part of the Water Pathways research cluster at the University of Toronto Scarborough. Her books include Language, Capitalism, Colonialism (with Monica Heller). Bonnie is of Irish, Slavic, German, French, and English descent. She grew up at the confluence of the Connoquenessing River and Glade Run, on Seneca, Lenape, and Shawnee territory, and is writing a book, The River Runs a Long Way Straight Here, about these rivers. Giidaakunadaad and McElhinny have held two previous grants together: Thirteen Moon Journey (Ontario Indigenous Cultural Fund) and Thirteen Moon Journey/Water Gathering (SSHRC Connection Grant for Building Indigenous Research Capacity/Reconciliation). In 2019, Giidaakunadaad and McElhinny participated in a national gathering sponsored by SSHRC to share insights on Indigenous research methodologies.

Email: bonnie.mcelhinny@utoronto.ca

- Indigenous Circle of Experts, We Rise Together: achieving pathway to Canada target 1 through the creation of Indigenous protected and conserved areas in the spirit and practice of reconciliation: the Indigenous Circle of Experts’ report and recommendations, (Parks Canada, 2018), iv, https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.852966/publication.html.

- Gidigaa Migizi (Doug Williams), Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg: This is our Territory, (ARP Books, 2018), 29.

- Anishinabek Nation, “Pre-amble to the Anishinabek Nation Chi-Naaknigewin”, SoundCloud, 2015, https://soundcloud.com/anishinabek-nation/ngo-dwewaangizid-anishinaabe.

- Read more about decolonizing and un-colonizing in “Decolonization, A Guidebook For Settlers Living On Stolen Land”, Unsettling America: Decolonization in Theory & Practice, April 3, 2021, https://unsettlingamerica.wordpress.com/2021/04/03/decolonization-a-guidebook-for-settlers-living-on-stolen-land/.

- See Call to Action #33, in the Final Report of the Steering Committee for the University of Toronto Response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, p. 30: “All divisions should be required to report annually to the Provost on progress in implementing University commitments in relation to the calls to action contained in this report.”

- For further reading, please refer to Adam Gaudry and Danielle Lorenz, “Indigenization as inclusion, reconciliation, and decolonization: navigating the different visions for indigenizing the Canadian Academy”, AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 14, no. 3 (2018): 218-227, https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180118785382.

- See Giidaakunadaad/Nancy Rowe, Debby Danard, and Bonnie McElhinny, Ceremony as Research: 13 moon journey, Working/policy paper submitted to SSHRC Conference for Building Indigenous Research Capacity and Reconciliation, 2019.