The following is the text of a talk given by Karen Chapple at the 3rd Urban Economy Forum, October 4, 2021

I sit here on land stolen from the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and the Mississaugas of the Credit, and there’s a good chance that most or even all of you are right now also on land that was stolen in some form. This might not always take the form of literally dispossessing others through colonizing the land. It might be that the land you sit on is stolen in the form of unearned gains, for instance, because there is a new transit line that increased the value of the land and gave the landowner a windfall. Or it might be stolen in the sense that the labor to build your house was undervalued, or that your office depends on the productivity of underpaid labor. Or it might just be that the system of rules and regulations governing how we use and extract value from land is unfair.

I bring up this notion of property because it is not possible to build sustainable and inclusive cities without addressing this fundamental dilemma. Inclusion means housing for all. And housing for all means that we need to address the displacement and human suffering that occurs because of the many ways in which property is theft. Democratic capitalism is a pretty good system for providing opportunity. But just as we need safeguards to make sure elections are fair, we need safeguards on the extraction of profit from land as well. As Joseph Stiglitz has argued, the unearned capital gains in land creates disparities in wealth that underpin inequality around the world.

Our ideas about ownership – and its corollary of theft and displacement – did not have to be this way. Even western cultures have debated the rules governing access to and control of land. Locke argued that property is a natural right, but the utilitarians like Hume argued that property was a product of civil society itself. Property upholds a set of values and relationships to land, and fosters utopian visions like the American Dream, where if you work hard, land and a home are the platform for opportunity.

But there are other ways of thinking about land entirely, and here we have a lot to learn from Indigenous peoples. Indigenous beliefs are diverse, but they share a radically different notion of our relationship to land and water. For Indigenous people, land and water are regarded as sacred, as living relatives. People are of the land and the land is of the people, and they are inseparable.

We cannot begin to have a discussion about how important it is to build cities and housing that are sustainable and resilient unless we confront these issues about land and wealth. And we cannot begin to confront systemic inequities in land ownership unless we can see them clearly. But they are obfuscated because of this issue of theft. Obviously, if you are taking something that is someone else’s, you don’t want to be seen. And so there are systems in place that make the theft of land invisible. One easy example is the financialization of housing, the commodification of housing that makes it easy for nameless corporations to buy, sell, and profit from residential buildings in distant places.

So let’s talk about ways to make the invisible visible. I see three important approaches here, and under me the School of Cities at the University of Toronto will be taking leadership in these.

The first is building a better understanding through different ways of thinking about land. We need to increase understanding of how land ownership has led to wealth and privilege through systemic and historic inequities. That means bringing in different areas of disciplinary expertise, not just economics, sociology, and geography, but also linguistics, art, ecology, computer science and more. And we need to support the different ways of knowing that these disciplines rely on. From the humanities, and from Indigenous cultures as well, we need to learn how to tell stories effectively, in ways that will be meaningful and legible no matter what your background.

The second is about data. The tragedy here is that we don’t have the data we need – we don’t have the data on housing and wealth to do the research, let alone tell the story. We don’t have good data on renting, anywhere in the world, while in most cities half or more of us rent. We don’t have data on who is buying, their race and ethnicity, gender, or income. We don’t always know when it’s a corporate buyer, or private equity firm, or even the price of the house. We cannot make the invisible visible without data.

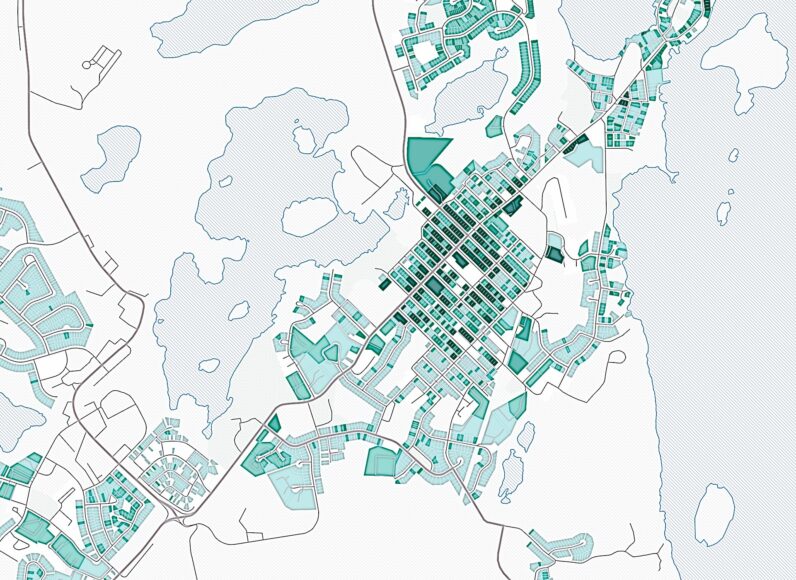

And the third is about mobilizing what we know in a more effective way. We need to highlight ongoing processes of exclusion, places in the city where the elite is extracting profit, places where the affluent are keeping others out. We need to do visualizations like we do at my research lab. We need to mobilize knowledge from across disciplines and utilize all the communication tools at our disposal.

So if we as a society want to move forward on truth, reconciliation, and restorative justice for all who have experienced theft – of their land, of opportunity, of the capability to realize their dreams – we need to build our capacity to make the invisible visible.